Dear friends,

We bring you two stories this week that are especially close to our heart—the controversy over school funding, which affects nearly a million working-class children and teens in NYC; and the work of immigrant artists representing the everyday worlds of migration, resistance, and strength. As a few trees in our neighborhood already begin to turn color, we wish you joy and good company during these last sips of summer. And we thank you for another season of engagement with the JHISN newsletter.

Newsletter highlights:

- Education (In)Justice? NYC School Budget Cuts

- The Art of Immigration Struggles

1. Who Are the Clowns?

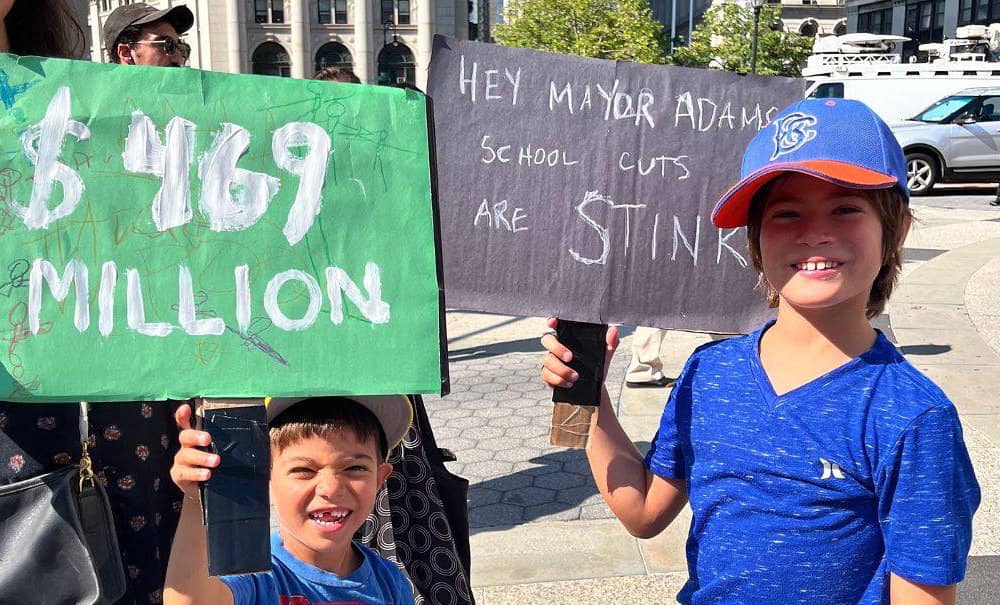

On Monday, July 11, several activists protesting deep cuts to the NYC public school budget were forcibly ejected from a Mayor Adams speech. “See, this is the clown,” the mayor quipped as they were dragged away. Among the people hustled from the room was a member of New Yorkers for Racially Just Public Schools, a social worker who just lost her school job, and an organizer with the immigrant justice group Make the Road New York.

The truth is that lots of people have acted like clowns in this year’s battle over public school funding—but it wasn’t these protesters. Instead, it’s the mayor, the city council, and a state appeals court who have brought a cruel circus to town, juggling with peoples’ lives and performing a high-wire act with the future of the city’s working-class children.

Perhaps no public institution is as important to New York’s immigrant families as the New York City Department of Education. Public schools are where generation after generation of immigrants have entered this city’s civic life, learned new languages, forged lifetime bonds with their peers of all nationalities, and gained the knowledge and skills necessary for social mobility. More than half of NYC public school students come from immigrant families. Non-immigrant working-class families also depend heavily on the school system. And yet our city, flush with federal stimulus money and higher than expected tax receipts, is poised to make savage cuts to school budgets—while adding $400 million to the NYPD. Seventy-seven percent of schools stand to lose up to a million dollars each. (PS 69 in Jackson Heights is slated to lose $558,995.) These cuts will force layoffs of guidance counselors, librarians, and teachers, along with increased class size and cancellation of after-school programs, art and music classes, and much more.

The pretext for these cuts is a decrease in school enrollment caused by the pandemic. Part of the funding formula for specific schools is based on the number of students who attend. But this is disingenuous at best. Students can’t be expected to flood back into the schools unless the city rebuilds the system, which has been badly damaged by unavoidable COVID disruptions, teacher and staff resignations, and years of underfunding. As City Comptroller Brad Lander has made clear, the money to rebuild is readily available. The federal government sent $7 billion in pandemic aid for NYC schools; $4 billion of it is so far unspent.

The City Council, donning its best clown suits, voted enthusiastically for the cuts, adopting the budget by a majority of 41 – 6. (Local Councilperson Tiffany Cabán, risking retaliation from the Speaker, was one of the few opposed.) Now, in the face of parent rage, the Council has changed its tune: members are claiming they were misled about the school budget and are demanding a do-over. The mayor insists on going ahead with the cuts and has been vigorously defending them in court. Schools Chancellor Banks says that Adams wants to “wean the schools off of the stimulus funding.” Known to be friendly to charter schools, Eric Adams doesn’t seem worried at all about the damage about to be done to regular public schools.

Throughout the battle over school funding, immigrant justice groups have helped lead angry protests. Local organizations DRUM and Make the Road (MTR) have been especially active in contesting the budget’s twisted priorities. Besides the July 11 protest during the Adams event, there have been rallies at City Hall, in Foley Square, and at schools such as our own PS 69. On June 17, demonstrators gathered outside the Jackson Heights school to decry “the city’s anti-student anti-community budget.” The People’s Plan coalition—made up of dozens of groups including DRUM, MTR, CAAAV Organizing Asian Communities, the NY Immigration Coalition, Sakhi, and MinKwon Center for Community Action—has done everything they can for months to focus public attention on the glaring inequities in the budget, especially its attack on working-class education.

As of this writing, the school budget cut juggernaut is still rolling along. Thanks to an August 9 ruling of the state appeals court, the legal challenges that parents initiated to stop school funding cuts are on hold until at least August 29—a week before school begins. Layoffs and cuts to school programming have already started. The Adams administration says it is “pleased” with the court’s decision.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Review The People’s Plan NYC program for education.

- Support local efforts to defend public education: DRUM’s Dignity in Schools campaign and MTR’s Education Programs.

2. Immigration and Art in Parallel

Art and migration have always found a place of synergy. In previous newsletters, JHISN highlighted this synergy in: the Homeroom exhibit at MoMA PS1; Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s We Are More project; Paola Mendoza’s Immigrants Are Essential memorial work; the Billionaire Scroll designed by Ange Tran; and the parking lot mural, Somos La Luz, painted outside the Queens Museum of Art.

Launched in 2016 just as Trump was inaugurated, the artist-led collective For Freedoms was established to examine the role of art in local, national, and global politics. In 2018 the group conducted its 50 State Initiative: artists created billboards in all 50 states bringing together political and artistic discourse; many of the works were created by or with immigrant artists or depicted immigrant themes. In 2020, For Freedoms collaborated with Blazay to create “They Are Us, Us Is Them,” a mural near the Queensboro bridge that reimagines Norman Rockwell’s “Freedom of Worship” with immigrant subjects and people of color.

This year, Detention Watch Network—a national coalition working to abolish immigration detention in the US—promoted art in activism by creating its first Artist in Residency program. For the inaugural year Miguel Lopez, a linoleum printmaker and community organizer based in Chicago, crafted a coloring zine based on the stories of ten incarcerated immigrants, whom he interviewed by phone. Each featured person is or has been detained in one of the #FirstTen detention centers targeted for abolition in DWN’s Communities Not Cages campaign.

“Immigrant detention should be abolished because incarcerating migrants will not end poverty in their home countries. Putting people in ankle shackles will not end the violence that they’re running away from. Digitally tracking and monitoring migrants will not stop the environmental disasters that capitalism created in their homelands. Immigrant detention, in all its forms, does nothing to support these families, it only exacerbates the harm they have endured.” —Miguel Lopez, Detention Watch Artist in Residency

Miguel’s zine celebrates what brings each person joy. In each piece, the detention facility in which they were incarcerated is being destroyed with objects that the subject uses in their work, or that give them happiness or strength. As a line art document, the viewer is invited to color between the lines and join in the process of destroying each detention center.

RAICES in Texas also has an arts program but partners with groups to create plays, documentaries, artworks, books, and movies to bring awareness to situations faced by immigrants. In an April 2021 collaboration with BAM, the Brooklyn Academy of Music, a train station’s Arrivals and Departures board was adapted to show the incarceration start time and release time from detention, or their time of death in prison. In the summer of 2019, RAICES also famously installed a series of dummies in cages around NYC representing detained immigrant children, using audio recordings of conversations and sounds from border detention centers, to protest Trump’s family separation policy.

In March of this year, Brown University’s Watson Institute exhibited the letters, artwork, and objects created by people detained at Stewart Detention Center in Georgia. Called Breaking Out, the activist art project featured items that were pleas for help, clothes, or legal support—and offered depictions of everyday life in detention.

Art will continue to find synergies with the realities and needs of immigrants so long as incarceration, deportation, the separation of families, and the denial of human rights are met by creative struggles for social and economic justice.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- View, self-print, and share Miguel Lopez’s zine, available in English and Spanish.

- Creatively experiment with the For Freedom projects Justice Collaboration Tool or Trust Fall.

- Check out the video about the making of a public mural by the art collective Amapolay and Peruvian artist Olinda Silvano.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.