Dear friends,

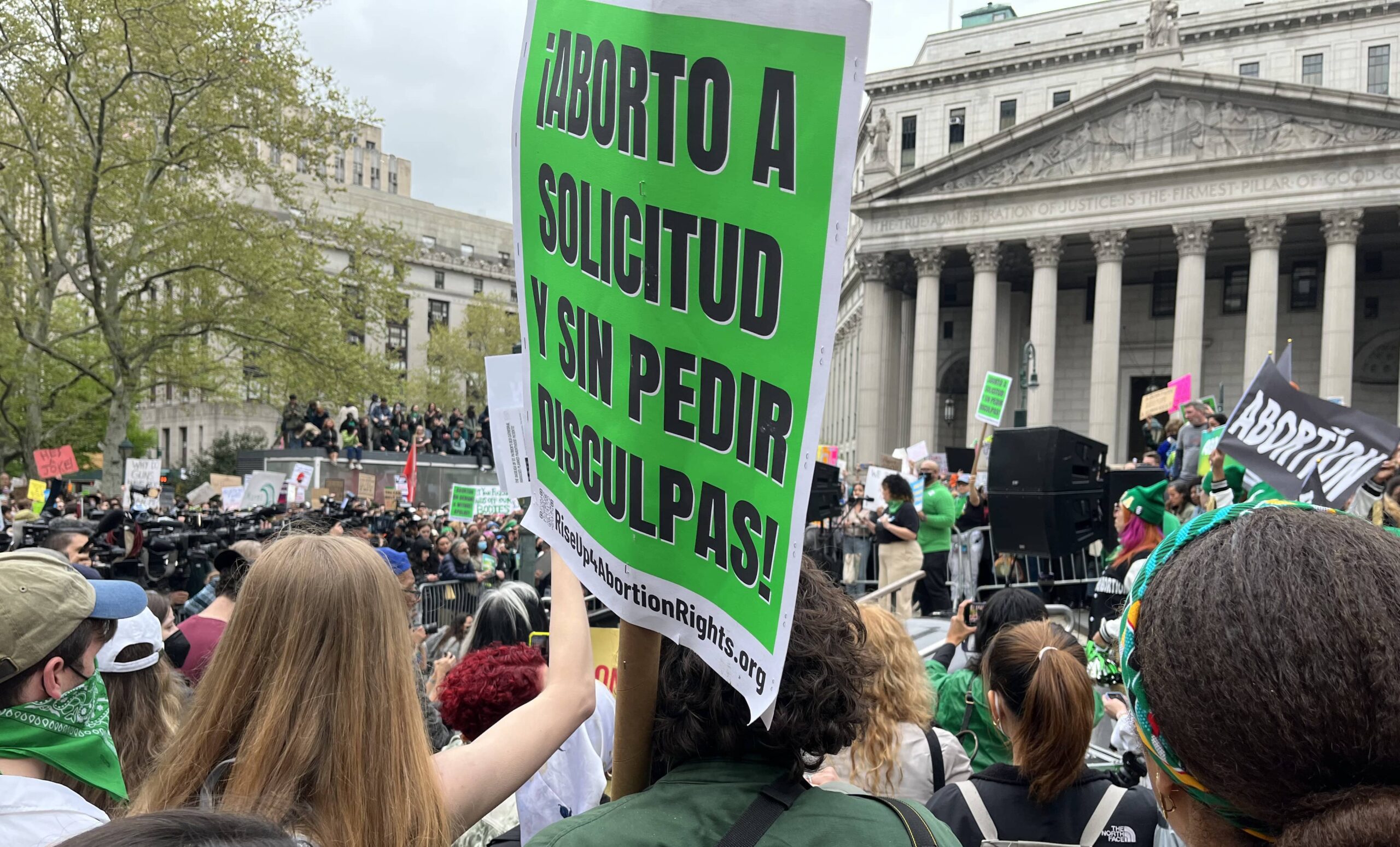

As the seasons turn, we return to a dramatic story that we covered in our last newsletter: the deeply local and global story of migrants being bused from Texas, Arizona, and Florida to northern sanctuary cities. Led by grassroots immigrant justice groups, New York City struggles to respond to the immediate needs of thousands of new arrivals. It is hard to think of a more important issue than how we can, concretely, create the structures and community that will embrace all migrants who find themselves living among us, here, in this city built by immigrant labor and immigrant cultures and immigrant power.

1. NYC response to red-state busing—refusing the anti-immigrant storyline

This weekend, historical documentarian Ken Burns premiers a film series on PBS about the Holocaust. Co-produced and co-directed with Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein, the trio highlight how Germany based its anti-Jewish laws on US Jim Crow exclusionary laws. The docuseries also shows how anti-immigrant sentiments shaped the stark fact that the US opened its borders to only a fraction of the hundreds of thousands of Jews seeking refuge from Nazi Germany. At that time, North Carolina’s Senator Robert Reynolds said, “If I had my way, I would today build a wall about the United States so high and so secure that not a single alien or foreign refugee from any country upon the face of this earth could possibly scale or ascend it.” Burns says he purposefully tried to leave it to viewers to see parallels of current-day attitudes to immigrants at the border with the past.

Fifty percent of Texans support Governor Greg Abbott’s current political spectacle that places asylum seekers crossing into Texas on buses to sanctuary cities in the north, including NYC. He attempted to secure funds via private donations for the charter bus rides so he didn’t face criticism for using taxpayer money, but so far has raised just over $300,000. His supporters may not realize that the bused migrants are more likely to be granted asylum in these sanctuary cities, or that his approach contradicts a fiscally conservative policy proclaimed necessary by the Republican party:

- According to TRAC analysis at Syracuse University, the newly-arrived migrants are more likely to have their asylum cases approved in New York City courts than in Texas. In the past 10 months, Houston judges approved only 17% of asylum cases and 33% were approved in Dallas. In NYC asylum was granted to almost 4 out of 5 applicants—over 82%.

- A Greyhound bus ticket from Texas to New York would cost an individual just under $300. Abbott’s taxpayer-funded coach rides average $1,300 per passenger, while Arizona’s chartered bus trips cost over $2,000. Immigration rights experts like Abel Nuñez, Executive Director of the Central American Resource Center, have pointed out that “the Republican governor who is working to crack down on illegal immigration is actually establishing one of the nation’s most generous publicly funded services to assist immigrants.”

As Abbott performs his public posturing by filling buses, NYC Mayor Adams and Manuel Castro from the Office of Immigrant Affairs are welcoming immigrants at the Port Authority. Their show is about fulfilling the city’s legal obligation to provide same-day housing for any adult who requests it, regardless of immigration status. They are enforcing the law by placing migrants in shelters and 14 hotels with the support of immigrant organizations and volunteer groups like Grannies Respond. However, not all migrants can secure places to sleep, especially if they want to remain as a family. Also, some Republicans in New York suggest that using hotel rooms in this way is hurting tourism, but the hotels themselves state they have the space since occupancy still lags behind pre-pandemic levels.

Murad Awawdeh, Executive Director of the New York Immigration Coalition, noted that some stories and images coming out of the Port Authority bus station were being falsely used to stir up bigotry and xenophobia. “Just to be clear, we’re not condemning Governor Abbott for busing people to New York City,” he said. “We’ve condemned him for busing people under misleading information to places that they do not want to go to. For treating people inhumanely.” Abbott’s decision to not send information to NYC about who was on the buses and when they would be arriving was, according to Awawdeh, a purposeful effort to create chaos.

Abbott has been looking to secure $4 billion for his border security efforts including Operation Lone Star which, deploying misinformation and criminalizing border-crossing, authorizes the Texas National Guard to arrest migrants who trespass on private property. New York City on the other hand launched Project Open Arms, a multi-agency plan to enroll over 1,000 migrant children in public school districts 2, 3, 10, 14, 24, and 30—which includes Jackson Heights. The children are placed in schools with low enrollments and given backpacks and supplies; their parents will be provided with MetroCards. School officials say that most of the children need intense language instruction, special education assessments, and mental health support.

In addition, New York’s Immigrant Advocacy Groups have promoted a $40 million dollar campaign called Welcoming New York, to cover medical services, interpreters, legal assistance, and resettlement services for the new immigrant population. The campaign aims to help “rebuild the welcoming system for asylum-seekers and refugees gutted during the Trump Administration.” Working at federal, state, and local levels, it seeks to create structures—beyond Homeland Security—that will support and sustain new arrivals to the US.

Despite such actions, NYC is not all-welcoming. A Republican Councilwoman in one Queens district announced that the immigrants should be further bused on to Greenwich, CT, instead of staying in hotels in her district. In some cases immigrants do not find the shelter system safe and choose to leave it; in one recent case, in Brooklyn, a security officer was suspended for striking one of the Texas-bused asylum seekers from Venezuela.

No one knows how this busing action might disrupt the asylum application process because it is unclear exactly how the migrants got onto the buses. They have 90 days to apply for asylum at their destination and the location to which they were bused may not be their final destination. Of the migrants bused to Washington, DC, around 10% didn’t have any contacts in the US. Some of the addresses on their paperwork were scribbled in by Border Patrol agents, and Abel Nuñez’s organization had to coordinate transportation for them to be returned to Texas. About 30-40% of people bused to New York City from Texas do not want to be here and need support to get to Louisiana, Ohio, Washington State, Oregon, Wisconsin, or even make their way back to Texas!

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Support the work of Grannies Respond with a donation, or by buying clothing on their website’s Target wish list link to support the care packages they hand out to people arriving on buses from Texas.

- Volunteer with the New York Immigration Coalition and download their immigrant power Blueprint for the Nation.

- Promote the NYIC’s Welcoming New York Campaign on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

- Determine how to use the Ken Burns Holocaust Classroom resources to elevate your pro-immigrant conversations.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.