Dear friends,

We welcome our readers to the Year of the Tiger, ushered in by over a billion people celebrating this past week’s Lunar New Year—including hundreds of thousands of Asian and Asian American residents here in Queens. JHISN marks the new year by a look back at the extraordinary work in 2021 of several local immigrant justice groups.

Many of us have seen the recent headlines about the fatal landslide in Quito, Ecuador’s capital city, after nearly 24 hours of continuous rain. Not all of us know that Ecuadorians compose the largest immigrant community here in central Queens. We offer a story about the history and recent increase in migration from Ecuador, which is also a story about Jackson Heights today.

Newsletter highlights:

- Migrant Paths from Ecuador to Jackson Heights

- Local Immigrant Justice Groups @2021

1. Ecuadorian Immigrants at JH’s Heart

“If you have dreams, you can fulfill them, as long as you feel proud of who you are and where you are going. The rest just depends on work.”

José Juan Paredes, Afro-Ecuadorian musician

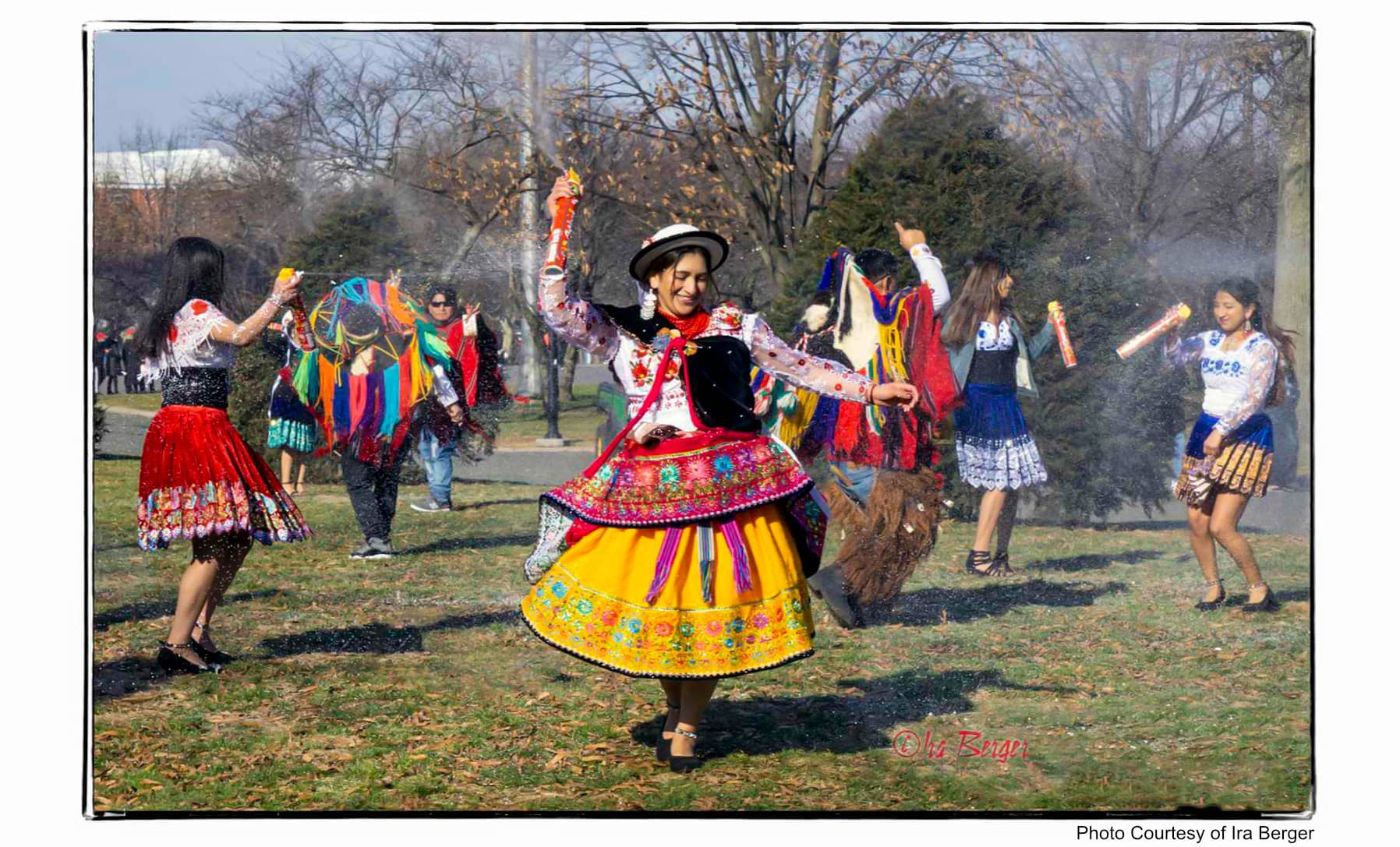

Ecuadorians make up the biggest immigrant group in our community: more than 100,000 in Queens and over 20,000 in the Jackson Heights area alone. In recent years, coronavirus and other factors have caused a new surge of migration that is bringing more Ecuadorians to our neighborhood.

Ecuador is highly diverse geographically, socially, and politically. Spanish, Quechua, Shuar, and other Indigenous languages are officially recognized. The northern Andean provinces were part of the Inca Empire and have much in common with Peru and Colombia, while there is a strong Afro-Ecuadorian culture in the Pacific coastal region. The eastern rainforest region is home to several Native peoples. And Ecuador is itself home to the largest refugee population in Latin America, mostly Columbians fleeing conflict in their own country.

Ecuadorians’ reasons for migrating to the US are diverse as well, but often involve economic crises. The first wave of migrants followed the 1947 collapse in the market for Panama hats (made by Ecuadorian women). A second wave of migration in the early 1980s was caused by an oil bust and economic crash that bankrupted many poor farmers. In the late 1990s, the national poverty rate climbed to 56% due to low oil prices, flooding, and political instability. Up to a million Ecuadorians emigrated in those years, out of a total population of roughly 18 million.

Now, Covid has set off another wave of migration. The pandemic devastated Ecuador’s already-struggling economy, causing the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs. The number of Ecuadorians arriving in the US reached its height this past summer: in July, US authorities stopped 17,314 Ecuadorians at the southern border, compared with 3,598 stops in January.

Other factors contributed to recent Ecuadorian migration. Starting in 2018, Mexico allowed Ecuadorians to enter without a visa. This offered Ecuadorians easier access to the US border. (Mexico canceled this policy in August 2021, making migration more arduous and hazardous.) Also, Ecuadorian nationals, unlike migrants from Central America, were not targeted for automatic exclusion under draconian Title 42 “public health” regulations. Finally, many Ecuadorians hoped that Joe Biden would be more immigrant-friendly.

Ecuadorians play an important role in the economy and culture of New York. Representing all social classes, they work as everything from professionals and business owners to day laborers cleaning houses. As we know, there are many Ecuadorian-owned restaurants. But also, undocumented Ecuadorian workers are a mainstay of NYC’s entire restaurant industry. Many Ecuadorian immigrants also work in construction, often doing the most dangerous and difficult jobs.

The Alianza Ecuatoriana Internacional (International Ecuadorian Alliance), located in Corona Plaza, is a respected community center for Ecuadorian immigrants. Founded by Walter Sinche in 1994 to combat violence and racism against Latin American immigrants, it has become a multifaceted non-profit that advocates for immigrant justice while also providing public health education and supplies, job training, and cultural activities including music and dance. The Ecuadorian American Culture Center, located in Long Island City, is another important institution for immigrants. EACC provides extensive cultural programming as well as tutoring.

Like many immigrant communities, Ecuadorian Americans are underrepresented in electoral politics. When Francisco Moya became State Assembly member for the 39th District in 2017, he was the first Ecuadorian American elected to public office in the US. (Moya currently represents District 21 of the New York City Council.) It will be interesting to see how Ecuadorian American votes influence local politics once NYC noncitizen voting takes effect in 2023.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Support the Workers Justice Project and their organizing work with Ecuadorian and other day laborers in NYC.

- Explore the Ecuadorian American Culture Center’s videos on the origin of Ecuadorian musical genres, and video profiles of Ecuadorian immigrants.

- Donate to relief funds for victims of the recent Quito mudslide in Ecuador.

2. A Year of Struggles and Victories // 2021

“In 2021 we came together in the face of compounding crises to take care of each other, and win what we needed to survive. We found ways to connect however we could, digitally over zoom, over the phone, and sometimes in person …. We built solutions even though everyone said it was impossible. We created the world we needed, one piece at a time.” – DRUM ‘Unite & Organize!’ video

We can’t begin to truly represent all that local immigrant justice groups have faced, and accomplished, during this past year of pandemic and political crisis. But we offer here a selective story that gives some sense of their inspiring engagement with community organizing, advocacy, and direct action.

DRUM (Desis Rising Up & Moving) is a member-led organization based in Jackson Heights that has been organizing South Asian and Indo-Caribbean working-class communities since 2000. Amidst ongoing commitments to gender justice work and their annual summer Youth Organizing Institute, DRUM in 2021 also built new solidarities and new organizational forms. Members participated in a solidarity hunger strike with taxi workers who finally won historic debt relief from the city. DRUM organized to bring South Asian and Latinx delivery workers together, building solidarity in the face of an exploitative, dangerous industry. And they launched a new sibling organization, DRUM Beats, to engage in electoral politics and creatively build ‘hyperlocal power.’

Adhikaar is a women-led immigrant justice group in Elmhurst serving the Nepali-speaking community since 2005. In July 2021, Adhikaar celebrated a historic victory: a bill dramatically expanding legal and economic protections for domestic workers passed the NYC Council. Adhikaar and coalition partners also introduced the NYC Care Campaign, aimed at gaining insurance and benefits for over 200,000 care and domestic workers—primarily immigrant women of color. Adhikaar helped lead the fight in 2021 for a New Jersey Domestic Workers Bill of Rights to secure legal rights for the state’s 50,000 domestic workers.

Adhikaar was invited to the White House in Summer 2021 to participate in a roundtable on immigrant rights with Vice President Kamala Harris. Closer to home, they continued to provide neighborhood relief during the ongoing Covid crisis, distributing Emergency Relief Funds to community members excluded from federal relief, and working with the NY Immigration Coalition to distribute food coupons to over 900 households.

The Street Vendor Project, representing about 2000 NYC street vendors, continued in 2021 to push for city legislation to decriminalize street vending and provide protections for an immigrant workforce that, literally, feeds New York. In May, the Street Vendor Project organized a well-publicized direct action at Hudson Yards where vendors had been displaced by the NYPD at the bidding of real estate developers.

In September 2021, when Hurricane Ida moved north and torrential rains slammed into the city, Queens Neighborhoods United (QNU) stepped up to provide mutual aid and financial support to immigrant households in central Queens devastated by basement flooding.

Make the Road New York (MRNY) organizes and empowers immigrant Latinx communities. Founded in 2007, MRNY has over 23,000 members and a local office right here on Roosevelt Avenue. In 2021, MRNY provided Covid information and outreach to 40,000 people; served 1,100 weekly at MRNY food pantries; and vaccinated 1000 at community center events. As leaders in the coalition struggle to Fund Excluded Workers, MRNY celebrated a huge victory with the first-in-the-nation state fund that delivered $2.1 billion to immigrant workers excluded from federal emergency unemployment and pandemic stimulus relief.

MRNY also helped win $500 million to create a culturally responsive curriculum reflecting the diversity of NYC students, and $4.2 billion in funding for school districts with high needs. After a decade-long campaign, Make the Road celebrated the repeal in 2021 of the Walking While Trans ‘loitering’ law that profiled and criminalized low-income TGNCIQ people of color. Looking ahead, MRNY launched plans in 2021 to open a new three-story, 24,000 square foot community center in Queens in 2022.

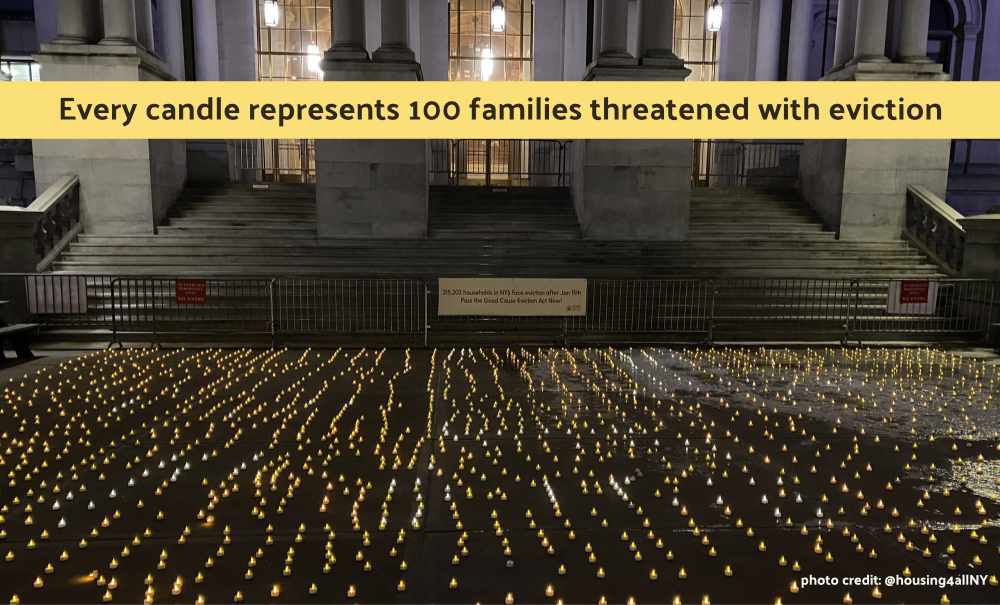

Chhaya CDC is another Jackson Heights-based organization, focused on housing and economic justice for South Asian and Indo-Caribbean communities. In 2021, when Hurricane Ida hit, Chhaya was poised to take a lead role in aiding immigrant households devastated by flooding and property damage. They knocked on more than 200 doors to provide resources, and distributed over $53,000 in emergency relief funds. Chhaya also organized multilingual community outreach (in Bangla, Hindi, Nepali, Tibetan, and English) about the Emergency Rental Assistance Program to aid households threatened with evictions due to the pandemic.

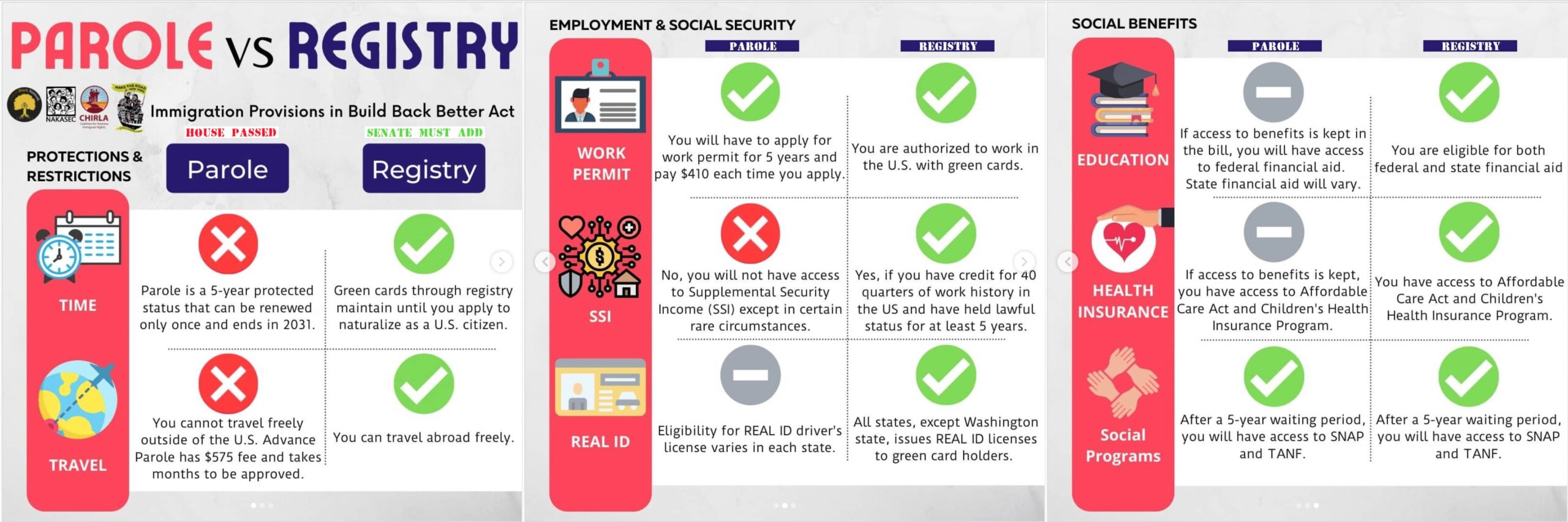

NICE (New Immigrant Community Empowerment) is an immigrant justice organization and day laborer worker center in Jackson Heights that has, for over two decades, offered solidarity and job training to newly arrived immigrant workers. In 2021, NICE amplified its role as a community organization, helping thousands of immigrant households to weather the pandemic by providing groceries, hot meals, accurate Covid information, and reliable vaccination locations. At the same time, NICE organized multiple rallies, vigils, and trips to Washington, DC to advocate for immigration reform. Their major campaign, 11 DAYS FOR 11 MILLION, demanded that the Biden administration keep its promise of citizenship for 11 million immigrants. In mid-November, the 11 days of action culminated in an 11-mile march that started at 110th St. and ended in Brooklyn outside Senator Schumer’s home.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- If you are financially able, consider supporting the work of any of the above organizations! Just click on the organization’s name and go to their DONATE page.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.