Dear friends,

May this Fall weekend find you in good health and spirits.

JHISN continues to learn and find inspiration from the resilience, diversity, and creativity of local immigrant communities. We hope that by sharing what we learn, this newsletter plays a small role in strengthening solidarity with, and among, immigrants.

In this week’s newsletter, we report on a new stage in the struggle of New York taxi drivers to secure debt relief and justice. The New York Taxi Workers Alliance has been demonstrating in front of City Hall around the clock for a month.

Our second story details the ongoing challenges facing residents of flooded basement apartments in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida. Many immigrants are confronted by extreme housing insecurity and serious health risks.

1. Taxi Workers Battle De Blasio Sellout

The struggle for debt relief by New York’s immigrant yellow cab drivers has entered a dramatic new stage. For almost a month, the New York Taxi Workers Alliance has held a continuous, round-the-clock demonstration outside City Hall. NYTWA leader Bhairavi Desai has declared, “We are not leaving the streets until justice is served.”

In our May 15 newsletter, we described how city agencies ripped off thousands of owner-drivers. First, they knowingly created an unsustainable bubble in taxi medallion prices and encouraged predatory loans, leaving drivers drowning in debt when the bubble burst. Then the city let tens of thousands of unregulated, no-medallion Uber and Lyft cars drive off with their fares. The pandemic delivered a final blow. Amid a wave of forced medallion foreclosures, nine drivers died by suicide.

Finding himself under mounting political pressure to correct this ongoing injustice, Mayor De Blasio continues to turn his back on the comprehensive, cost-effective plan for relief put forward by the New York Taxi Workers Alliance—a plan widely supported by local progressive politicians. Instead, he’s made a backroom deal with bankers, hedge fund owners, and unelected bureaucrats at the city’s Taxi and Limousine Commission—the same body that enabled the crisis to begin with. The resulting “TLC Taxi Medallion Owner Relief Program” includes some debt relief. But it falls far short of what the drivers are calling for, is structured to serve the lenders, and would cost the city more than the drivers’ plan. It’s being rolled out in a rush, before its own rules are even finalized, to try to stifle criticism.

The average debt of individual medallion owners is $550,000. The TLC plan proposes to give tens of millions to the banks in return for writing down a portion of this debt. As they are well aware, this would still leave unsustainable loan balances of hundreds of thousands of dollars for most owner-drivers. The city has declared that it hopes to get many driver payments down to “only” $1,600 a month. According to the NYTWA, that would keep drivers’ net income well below the minimum wage. More bankruptcies would be inevitable.

The drivers’ plan calls for restructuring all driver loans down to no more than $145,000, with monthly payments at or below $800. If there is a defaulted loan, the city would take over the medallion, and resell it. It would then pay any remaining balance owed to the mortgage holder. Most of the cost of the NYTWA plan would be borne by predatory lenders, not the city. Cost estimates of the taxi drivers’ plan, verified by the city comptroller, are around $3 million a year, compared to the $65 million short-term costs of the De Blasio plan. The NYTWA plan also includes provisions to help older drivers to retire, as well as to give drivers who have lost their medallions through foreclosure a chance to regain them.

NYTWA cab drivers, almost all immigrant workers, are fighting for a real debt relief solution, refusing to be manipulated or diverted by the mayor. They’re out in front of City Hall all day and all night, rain or shine—picketing, chanting, giving interviews, and lighting candles at memorials for their deceased fellow drivers.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Join the NYTWA 24/7 protest at City Hall (Broadway & Murray)—stop by, take pictures & tweet at @NYCMayor and tag @nytwa.

- Donate to support NYTWA organizing, and sign NYTWA’s online petition

- Call Mayor De Blasio and tell him that we need real relief for drivers. Click here for a phone number and script.

2. Living and Dying Underground

“They’re often immigrants, they’re often people of mixed-status families. They are the essential workers. They are the lowest wage earners … The most vulnerable New Yorkers live in basement apartments.” —Annetta Seecharran (executive director, CHHAYA)

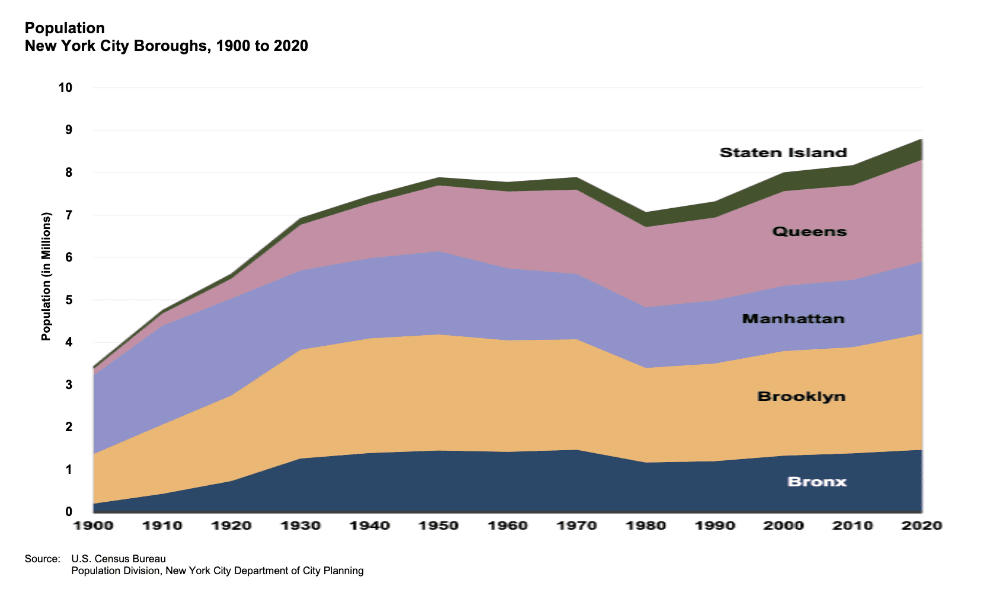

The news headlines have faded, but fallout from the torrential rains brought to NYC by Hurricane Ida on September 1 continues to accumulate. While the shadow economy of underground basement apartments in Queens has been invisible to many of us, the devastating effect of Ida’s flooding on basement residents is impossible to ignore. At least 11 people in Queens died during the unprecedented storm, drowned in basement dwellings, trapped in rising floodwaters. Now, uncounted numbers of immigrants, many of them undocumented, find themselves without their belongings, facing potential homelessness and health threats from mold and fungus, as the effects of the storm slowly unfold.

An estimated 100,000-200,000 New Yorkers live in unregulated basement dwellings. Local community groups like Chhaya have fought for years to legalize and bring up to code the vast network of underground rental units in Brooklyn and Queens. But while that struggle for safe, affordable basement housing continues, many low-income people, including tens of thousands of essential workers, don’t have any good options. They are forced—literally—to move underground to survive economically and maintain a roof over their heads. On September 1, that survival strategy turned fatal for some, while thousands more now endure the slow disaster of post-flood life.

Oscar Gomez and his family are Queens residents whose basement home, belongings, and cash savings were largely destroyed in the flooding and its aftermath. “Swarms of fruit flies, first drawn by the mold growing on the basement walls, have now migrated to the floor above.” More than a month after the disaster, as the family continues to search for an affordable rental, the psychic trauma also lingers: “‘The fear is there, the worry, the uncertainty,’ Gomez said. ‘As soon as it starts raining, you can’t sleep’” (gothamist, 10/13/21).

Excluded from federal storm relief, undocumented New Yorkers hit by the storm learned in late September that they could apply for aid through a $27 million fund set up by the state and the city. In the first week of October, the City Council passed a bill requiring City Hall to create a comprehensive plan addressing the growing threats of climate change. The legislation highlights the vulnerabilities of working-class neighborhoods—like those in Brooklyn and Queens most damaged by Hurricane Ida—and not just the Financial District and coastal Manhattan.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- For undocumented New Yorkers excluded from FEMA assistance, check out local resources here. Contact Make the Road NY/Jackson Heights for direct assistance, or call the NYS hotline at 1-800-566-7636. Application deadline for NYS disaster relief for undocumented households is November 26.

- Both homeowners and tenants can access FEMA assistance and other flood resources on Chhaya’s website here.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.