Dear friends,

Welcome to our new readers! JHISN has been sharing our newsletter leaflet the last few weeks at the Jackson Heights Green Market. We are excited to build out our free subscribership to the newsletter — beyond the 500 loyal folks (amazing!) who are already with us. Please circulate our newsletter subscribe link to your neighbors and friends who might want to join. And please contact us at info@jhimmigrantsolidarity.org if you have a good idea for a local immigration story.

Today’s newsletter offers a look at the emerging demographic picture in Queens after a surprisingly successful 2020 census count, thanks in part to months of work and outreach by immigrant justice organizations. We then try to understand the deepening crises around state borders and mobility, as tens of millions of people are forced to leave their homes seeking–but often not finding–refuge and a safer haven.

Newsletter highlights

- Census results: NYC immigration groups shape who counts

- Refugee crises deepen in the US and globally

1. Immigration Advocacy Groups Helped Save the NY Census Count

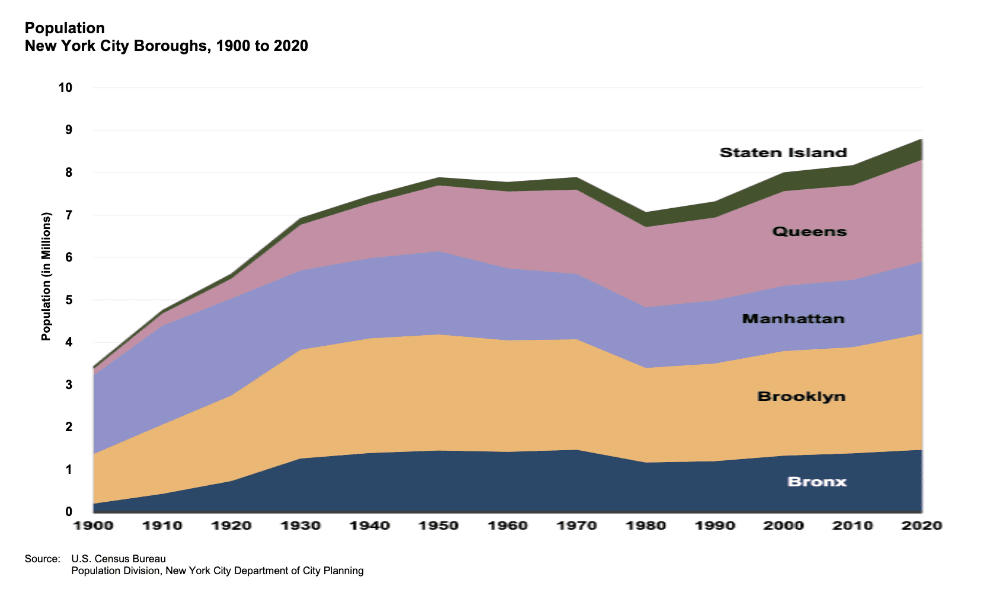

Last year, as the 2020 Census count began in earnest, there was widespread concern that a population decline over the last ten years, combined with a typical undercount of hard-to-count populations, might cause New York State to lose 2 of its 27 seats in the US House of Representatives. But thanks to heroic efforts by grassroots community groups to count everybody, the city exceeded its expected self-response rate and the state only lost one seat. No seats would have been lost had just 89 more people been counted!

This past week, 2020 redistricting data became publicly available, and local organizations can start to see the results of their work encouraging people in their communities to complete the census forms. A more complete picture will emerge about the demographics of our community, supplementing the information already available about Queens:

- In 10 years, the Queens diversity index grew by an insignificant half percentage point to 76.9%.

- Queens is still the most diverse county in NY State, but fell from the 3rd to the 6th most diverse county in the US.

- A 5% drop in the white population, replaced with a 5% growth in the Asian population, has led some to forecast a growth of Asian political influence.

- The Hispanic/Latino population is now the largest in Queens, with the Asian population just a half percentage point behind. The white population dropped from the first to third-largest group.

- Queens’ overall population growth of 7.8% since 2010 was higher than the 7.7% of NYC overall, but lower than Brooklyn’s 9.2%.

There are always concerns about the impact of a census undercount when using the Method of Equal Proportions, which has been in place since 1941, to determine how many congressional seats each state gets; it is the fifth approach to apportionment since the US census began in 1790. In addition to the regular challenges every decennial census faces to count every person, there were extra factors including the pandemic putting an accurate 2020 count at risk. The Supreme Court had to block the Trump administration from including a citizenship question, which would likely have prevented many immigrants from participating. After that failed, Trump released a memorandum instructing the removal from the apportionment base of people without legal immigration status. There was no practical way to meet that memorandum’s empty directive this time, but the future possibility of such a threat remains.

Exclusionary attempts to remove immigrants from the census were not unique to the Trump administration. Since its creation in 1979, the hard-line restrictive immigration group with the ironic acronym FAIR (Federation for American Immigration Reform) has pushed the government to ignore its constitutional duty to count all people in the US. To date, such efforts have been successfully countered by actions to effect a true count of all people.

The brazen attempts to undermine a true count underline the significance of the massive grassroots census activism that took place in New York. In particular, local immigrant justice organizations adopted the Census as a central priority to be sure their communities are seen. There has been extensive media reporting on the funding distributed to several local immigrant support groups by the federal, state, and city governments to assist with those grassroots efforts. But in reality, organizations such as Adhikaar, African Communities Together, Asian Americans for Equality, CIANA, Chhaya CDC, DRUM, and Make the Road NY–many of them groups serving immigrant communities in central Queens–ended up spending their own money and time to encourage the people in their communities to be counted.

The government did assist with multi-lingual printing costs and hard-to-miss t-shirts. But there were significant limits placed on what else could be funded. Certain types of groups could receive money, but bureaucratic criteria prevented many other groups from applying. Those who did apply had limits on what they could spend. No software could be purchased, no awards could be given for filling out the census, and no mobile computing devices worth more than $500 could be bought. Any money spent before March 10, 2020, for those groups who started early, was not reimbursed.

In the end, these local efforts resulted in census numbers that exceeded expectations. Some speculate that post-census redistricting will bring positive changes, such as the possibility for Little Manila, currently split between three districts, to have better representation. However, we have to wait until people can dive into the newly-released data to understand the changes and to see what impact there might be from knowing, for example, that “300,000 New Yorkers said they belong to two or more races, roughly double the number from 10 years ago.”

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Check out the interactive NYC Department of City Planning’s Reconfiguration of statistical geographies, which aids Community Boards and others to see updated Neighborhood Tabulation Areas data.

- Look at the NYC Population FactFinder in October when it is updated with the 2020 Census data.

- Participate in upcoming meetings of the NY State Independent Redistricting Commission. The commission should release its draft congressional and state legislative maps in mid-September and the Queens County Review Meeting is set for November 17.

2. Refugee Crises Out of Control

The statistical picture is unfathomable. In 2020, over 82 million people worldwide are geographically displaced by war, violence, climate catastrophe, and persecution. Girls and boys under the age of 18 make up 42% of that total. Forty-eight million people are internally displaced within their own country. Over 26 million are refugees, fleeing across borders. Just over 4 million people are asylum-seekers. And one million children have been born as refugees from 2018-20.

As the pandemic started to rage in 2020, 160 nation-states closed their borders, with at least 99 countries refusing to accept migrants seeking protection. Refugee resettlement has plunged dramatically, with only 34,000 people resettled worldwide last year. Nine in ten refugees are now hosted by low and middle-income countries with limited resources and infrastructure.

Despite the declarations of the United Nations’ 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees, and despite the ambitions of the UN’s 2018 Global Compact on Refugees, in 2021 there exists no formal global recognition of refugee rights, nor even a legally binding international definition of “refugee.” In many of the world’s refugee-hosting countries, refugees have no legal status at all. Their rights are under increasingly vicious attack in many countries, even as the conditions that force them to leave their homes become more dire.

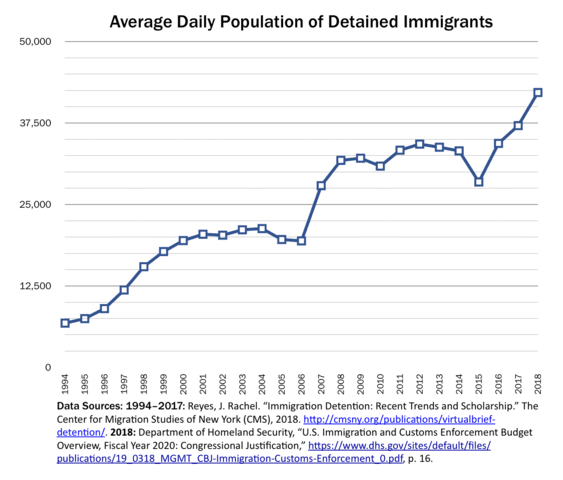

Just this week, the Global Strategic Litigation Council for Refugee Rights was launched. They aim to establish transnational legal standards for addressing the plight of refugee populations, and to establish the right to be free from immigration detention, which has become widespread in the US and globally.

But. The news on the ground is not good. By FY 2020, the Trump regime lowered the refugee admissions ceiling in the US from 85,000 in 2016 to a mere 18,000 (with less than 12,000 refugees actually admitted), and then set the FY 2021 admissions quota at 15,000. The Biden administration initially maintained that ceiling but, under political pressure, raised it to 62,500. Yet as of July 2021, only 4,780 refugees had been admitted to the US.

The US’s chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan has set off a massive refugee crisis. As the headlines blare, tens of thousands of Afghans have entered the US, temporarily ‘housed’ at US military bases. Tens of thousands more remain precariously in transit in Qatar, Spain, Germany, and Kuwait. But the largest population of Afghan refugees are those left behind in the implosion of the US’s decades-long military occupation. Hundreds of thousands of women, men, and children are fleeing their homes to seek safety from civil war and right-wing terror in another part of Afghanistan, or in neighboring countries, including Iran and Pakistan.

The refugee situation among Haitians, while garnering fewer headlines, is also grim. Under pressure from serial climate disasters and the political assassination of Haiti’s president, Haitian migrants are surging along the US-Mexico border in search of refuge. In the border town of Del Rio, Texas, in just the past few days, thousands of Haitians have gathered under a bridge for protection from the sweltering heat, sleeping in the dirt, without food, sanitation, or clean water. The Biden administration has announced it will begin putting migrants on return flights to Haiti starting Monday, September 20, to “signal to other Haitians that they should not try to cross the southern border.”

Immigration rights groups have slammed the Biden administration for continuing to use an obscure Title 42 regulation, put in place in March 2020 by the Trump regime, to expel tens of thousands of asylum seekers using a phony “public health” pretext. (News flash: A federal judge has just ordered a halt to this practice.) And the Women’s Refugee Commission along with over 100 other groups, has demanded that the Administration stand up to the Supreme Court’s decision to reinstate the (misnamed) Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), popularly known as the “Remain in Mexico’ policy. The policy has to date prevented over 70,000 people from claiming asylum in the US while stranding them in inhumane and dangerous conditions in Mexico.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Attend Rise and Resist’s Thursday immigration vigils protesting Biden’s extension of Trump’s anti-immigration policies.

- Donate to the Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan (RAWA). RAWA has organized resistance to the Soviet and US occupation and also to the Taliban and other right-wing criminals. They establish underground schools for women and children in Afghanistan, and provide education, medical care and other support for families in Pakistani refugee camps and for internal refugees.

- Sign the Domestic Workers Alliance petition to stop Haitian deportations.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.