Dear friends,

Amidst the cascade of immigration news at the national level (executive orders, new DHS/ICE/CBP appointments, policy reviews, and more), we take a look this week at immigration politics closer to home. As the pandemic deepens our relationships with our neighbors and our local communities, JHISN investigates a major change in how we vote in New York City: ranked choice voting. Thousands of Queens residents already cast votes in a special election this week that, for the first time, will be decided by ranked choice. As this new voting method becomes the rule, the promise, and risks, for immigrants are still coming into focus. We hope the newsletter helps us begin to unravel the complexities, and together create a local politics committed to immigrant justice and solidarity.

It’s not too late to contribute to our ‘Neighborhood Emergency!’ fundraising campaign. Our website links you directly to the donation pages of six local, frontline, immigrant-led organizations that are fighting for community empowerment during the pandemic. Whatever you are able to afford can make a real difference, in Jackson Heights and beyond.

Ranked choice voting: hope and concern from immigrant advocates

Ranked choice voting (RCV) has been billed as a way to ensure that all New Yorkers—especially immigrants and other underrepresented groups—have a voice in local elections.

But with a pandemic rollout, a fast-approaching mayoral primary, and several special elections already underway —including here in Queens—many people worry that the new RCV system will bypass the groups it’s supposed to benefit.

Nearly three-fourths of New York City residents who voted in 2019 approved ranked choice voting. The system applies to primary and special elections, including this week’s special election in Queens’ 24th District. (An official winner has yet to be called, but Democrat James Gennaro has all but secured the race with more than 50% of the votes.)

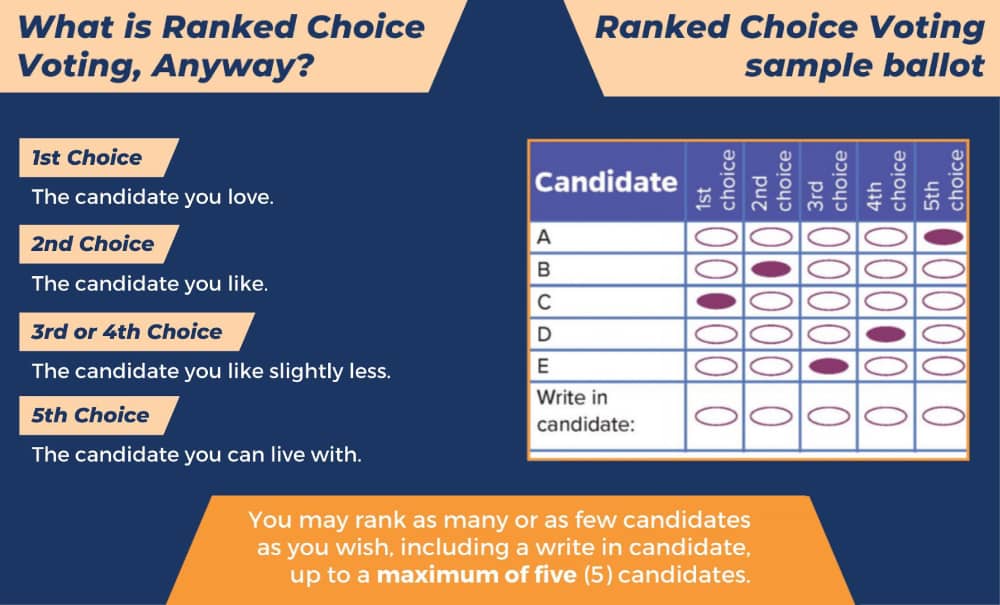

Here’s a brief explanation of how ranked choice voting works:

- Rather than casting your ballot for one candidate, you rank candidates with a first choice, second choice and so forth, up to five.

- If no candidate gets 50% or more of the (first-choice) votes, the candidate with the fewest votes is removed from the race.

- If you listed the removed candidate as your first choice, your ballot will instead be counted toward your second choice.

- The process repeats until one candidate ends up with more than 50% of the votes.

Advocates in New York who support the change, including the New York Immigration Coalition, say it will encourage candidates to reach beyond their bases to court second, third and fourth spots on voters’ ballots.

A widely cited 2018 study found that in California races with ranked choice voting, more candidates of color participated, and more women of color won local elected office. The authors hypothesized that the RCV system encourages a more diverse array of candidates, since candidates don’t have to worry about splitting the vote with competitors of similar backgrounds so none of them win.

But springing a brand-new voting system on residents during a pandemic—in a mayoral election year—doesn’t sit well with some, especially those advocating on behalf of communities that are often left out of public outreach efforts.

“When it became apparent that the Covid-19 pandemic would constrain its ability to enable a ‘robust voter education plan’ for this new and complex system, the city should have accelerated the pace of its efforts to execute its public outreach plan,” the City Council’s Black, Latino, and Asian Caucus said in a December statement. They argued that without adequate education, the system risks disenfranchising residents of color, seniors, and people who speak limited English. Several caucus members were among those that filed a complaint with the New York Supreme Court.

Despite the criticism, the Supreme Court refused to nix ranked choice voting for the special election in the 24th District. Meanwhile, several stakeholders in that election also voiced their support for RCV.

“If immigrants can handle the challenges they face on a daily basis, like operating in their second or third language, navigating government bureaucracies, or even learning to vote the traditional way in their non-native country, we are confident they will be able to rank their preferences in an RCV election, just like everyone else,” advocates from Jackson Heights-based Chhaya and the Chinese-American Planning Council wrote in an op-ed in the Queens Daily Eagle. In January, Chhaya and other community groups were out in the streets and online educating residents in eastern Queens about the new voting process.

The 24th District election could have led to the City Council having its first South Asian member. But that seems unlikely to happen at this point. There were complicating factors on top of the pandemic, including low turnout and the election date falling during a major snowstorm.

“There are 66,000 of us in Queens….And we don’t have representation,” said Moumita Ahmed, a Bangladeshi American and a prominent City Council candidate in the 24th District, in a Gothamist interview. “Ranked choice voting is literally the only way our voices can matter, can be heard.”

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Learn about ranked choice voting and talk to family and friends to make sure they know how it works. The city’s finance board explains RCV, with information in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, and Bengali.

- For those of us who are voters, start researching candidates for the November 2 City Council, District Attorney, Mayor, and other races, many of which will be effectively decided in the June primaries. Early voting for the primaries begins on Saturday, June 12. Registration must be completed by May 28, and absentee ballots must be requested by June 15.

- Listen to Jagpreet Singh, lead organizer at Chhaya CDC, discuss RCV on a recent WNYC Brian Lehrer Show.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.