Dear Friends,

Greetings to you as spring returns to warm us all again. We are learning how to change seasons in a pandemic. How to celebrate the holy month of Ramadan while physically distancing. How to have birthdays while staying-at-home.

We will mark Memorial Day in the shadow of over 6000 coronavirus deaths in the borough of Queens; 1200 deaths in Jackson Heights and neighboring areas. With terrible clarity, we know that people are dying more often in immigrant communities, working class neighborhoods, and communities of color throughout New York City. How can we memorialize this almost unimaginable loss? How do we struggle together locally for immigrant rights, and economic and racial justice, so that we are all protected equally from the ravages of a global pandemic?

Newsletter highlights:

- Urgent Need for Deportation Moratorium

- NICE Fights for Recently-Arrived Immigrants and Leads in Local Food Support

- Food Politics are Immigration Politics

1. End Covid Cruelty — Stop Deportations Now

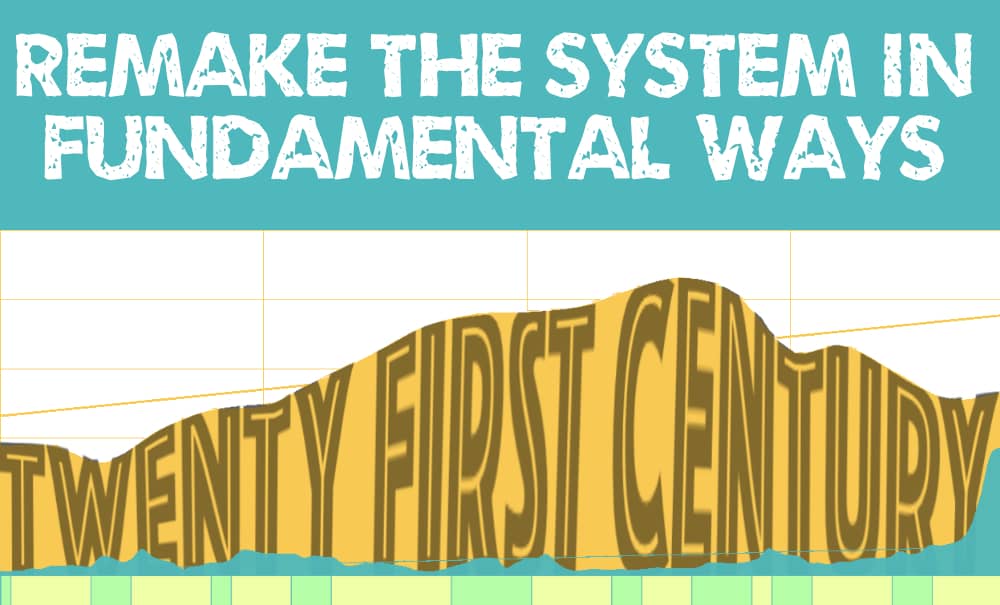

Our newsletter readers are aware that immigrants have been subjected to staggering forms of discrimination and abuse during the Covid-19 epidemic. Immigrants face higher rates of infection, hell-hole conditions in detention centers, racist attacks in public, denial of unemployment benefits and urgently-needed aid for immigrant households, small businesses and undocumented people—the list goes on and on. What’s also become clear is that the Trump regime is using the coronavirus as a pretext for achieving what it always wanted: to exclude and deport as many immigrants as possible.

The Trump administration now denies entry to virtually all refugees, supposedly because of the pandemic. But this is only their latest attempt to manipulate “public health” issues to seal US borders. In 2018, the architect of Trump’s most vicious anti-immigrant policies, Stephen Miller, used an outbreak of illnesses and deaths in unhealthy detention centers to attack immigrants. In 2019, he again highlighted “health concerns” with immigrants when mumps broke out among detainees. Later that year, he politicized a flu outbreak at Border Patrol stations. In each case, Miller hoped to leverage the extraordinary powers given to the president in times of public health emergencies. With COVID-19, he and Trump have hit the jackpot:

The administration has weaponized an arcane provision of a quarantine law first enacted in 1893 and revised in 1944 to order the blanket deportation of asylum-seekers and unaccompanied minors at the Mexican border without any testing or finding of disease or contagion. Legal rights to hearings, appeals, asylum screening and the child-specific procedures are all ignored.

More than 20,000 people have been deported under the order, including at least 400 children in just the first few weeks, according to the administration and news reports. Though the order was justified as a short-term emergency measure, the indiscriminate deportations continue unchecked and the authorization has been extended and is subject to continued renewal. (NYTimes, May 11, 2020)

Meanwhile, green card applications for 358,000 people trying to join their loved ones in the US have been frozen. In a private phone call, Miller clued in his supporters that this “temporary” Covid-19 order is part of a larger strategy to reduce overall immigration.

Despite obvious health dangers, deportation from ICE detention facilities grinds on in the form of dozens of flights to Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. Many deported immigrants are Covid-positive, meaning that the US is effectively exporting the virus. This exposes the ultimate in hypocrisy: a regime claiming to act because of a health emergency is causing the pandemic to spread around the world. In a bitter rebuke, the Health Minister of Guatemala has labelled the US “the Wuhan of the Americas.”

The United Nations Network on Migration has called for the suspension of migrant deportations during the pandemic. Doctors Without Borders insists that the US halt deportations to Latin America and the Caribbean. And a coalition of more than 100 groups has demanded that Trump stop deportations to Haiti. JHISN has long called for a moratorium on all deportations and migrant detentions. Today this call is more critical than ever.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

2. NICE: Fighting for Low-Wage Immigrant Workers

Several weeks ago, the New York Times reported on Manuel Castro’s dilemma with food distribution. Castro, the executive director of NICE (New Immigrant Community Empowerment), had secured 100 boxes of food to distribute to the immigrant day laborers and domestic workers the group supports. But who should get it? His method of selection was randomly fair, and by no means preferential. Names were pulled from a hat.

One month later, the Jackson Heights-based NICE is still working on food distribution to thousands of Queens residents excluded from COVID-19 federal stimulus, unemployment, and other supports because of their immigration status. This time the NICE4workers team are working alongside local street food vendors, labor unions, and State Senator Jessica Ramos, giving out free fresh food secured from New York state farms. NICE also partners with the NGO Khalsa Aid USA–founded on the Sikh principle to “Recognise the whole human race as one”–bringing healthy grains, lentils, beans, vegetables, fruits, and rice (in a reusable canvas tote!) to undocumented families in Jackson Heights.

Somehow, NICE also finds time to actively protest wage theft and exploitation of immigrant workers with their #TakeItBack campaigns. With a membership composed largely of newly-arrived immigrants, and undocumented immigrants in the construction and landscaping industries (including a growing number of women transitioning to construction work), NICE organizes some of the most vulnerable and precarious workers in NYC.

No one was truly prepared for this pandemic. But NICE was ready to take action, with its founding purpose to “prioritize the leadership and voices of low-wage undocumented immigrant workers who are often excluded and/or marginalized from other spaces.” Low-wage undocumented workers have been multiply marginalized during the pandemic crisis, receiving no federal support (even when deemed ‘essential’ workers), and having to fight for resources from state and city agencies–all while continuing to risk hard physical labor when other New Yorkers have the luxury of working remotely and remaining physically isolated.

NICE promotes the welfare of their members with regular Occupational Safety and Health training programs, focussing attention on employees’ legal rights in the workplace. NICE also provides job training videos on subjects like plumbing, painting and English-language wording commonly used in the construction industry. They have ensured that COVID-19 information is available to workers in their own language.

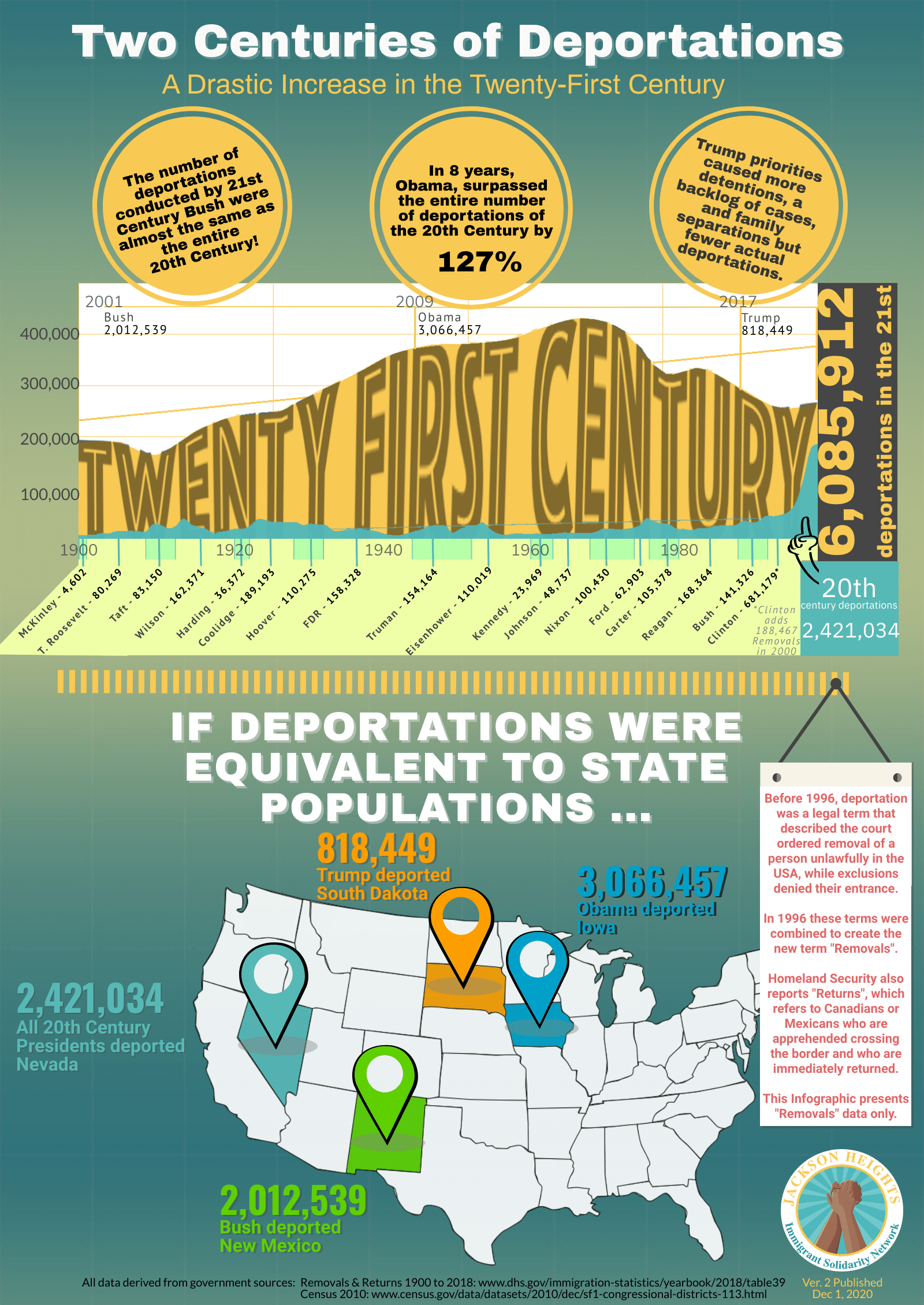

NICE recently supported the May 20 Town Hall demanding an Excluded Workers Fund in New York State. Working with a coalition including New York Communities for Change and Make the Road NY, NICE is calling for a $3.5 billion state relief program, funded by taxing billionaires and corporations, to support immigrants who have been systematically excluded from government assistance legislation. Meanwhile, one of the founding members of NICE, Jessica González-Rojas, is running for State Assembly District 34.

On May 19, NICE announced that almost $4,500 was raised from 64 donors to fund NICE’s front-line community support efforts. JHISN applauds the sustained efforts by NICE to support, train, advocate for and provide services to our immigrant workers, fighting for an economy that works for everybody.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

3. Food, Immigrant Labor, and the Politics of Hunger

The signs are clear: lines for local food banks in Queens stretching for blocks, reports that one in four New Yorkers now lacks adequate food, higher food prices just as more people have less money to spend. Hunger and food insecurity are not new in our city, but the pandemic and its economic fallout have placed an estimated 2 million New Yorkers at risk of not having enough to eat. In Jackson Heights, mutual aid work by immigrant-led community groups is focused increasingly on food assistance.

While the city promises to increase its pre-made meal distribution program to 1.5 million meals each day, mutual aid groups in Jackson Heights note that most immigrant households need groceries and staples for cooking—not pre-made meals. Nourish New York, a $25 million state initiative drawing from public health emergency funds, allows local food banks across NY to purchase agricultural products from upstate farms that were being ‘dumped’ by desperate farmers. In central Queens, over 30,000 pounds of upstate farm food is being distributed weekly in food bank and hot meal programs organized by State Senator Jessica Ramos’s office.

While food insecurity in NYC is certainly not limited to immigrant communities, there are deep challenges immigrant households face as hunger threatens more of us, including accessing resources and provision of culturally-appropriate food. Even before the coronavirus crisis, the number of low-income immigrants nationwide signing up for food benefits was dropping, as recent changes to the ‘public charge’ rules governing legal status for immigrants threaten to disqualify those who access public benefits. Fear is spreading among immigrant communities that any kind of government assistance—even food aid during the pandemic—can block their path to legal status. The anti-immigrant policies and rhetoric of the Trump regime feed that fear, even as immigrant households grow hungrier.

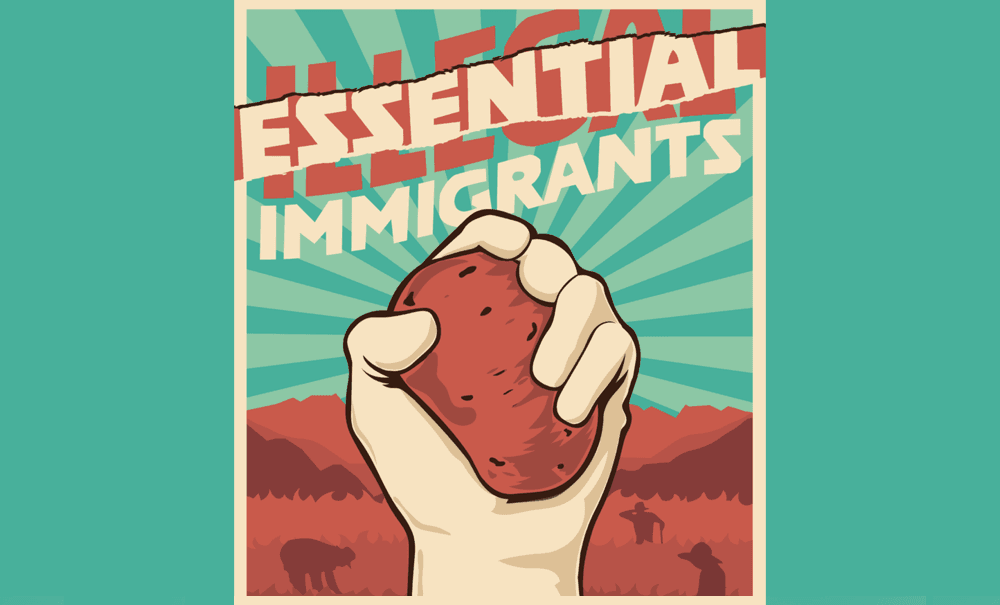

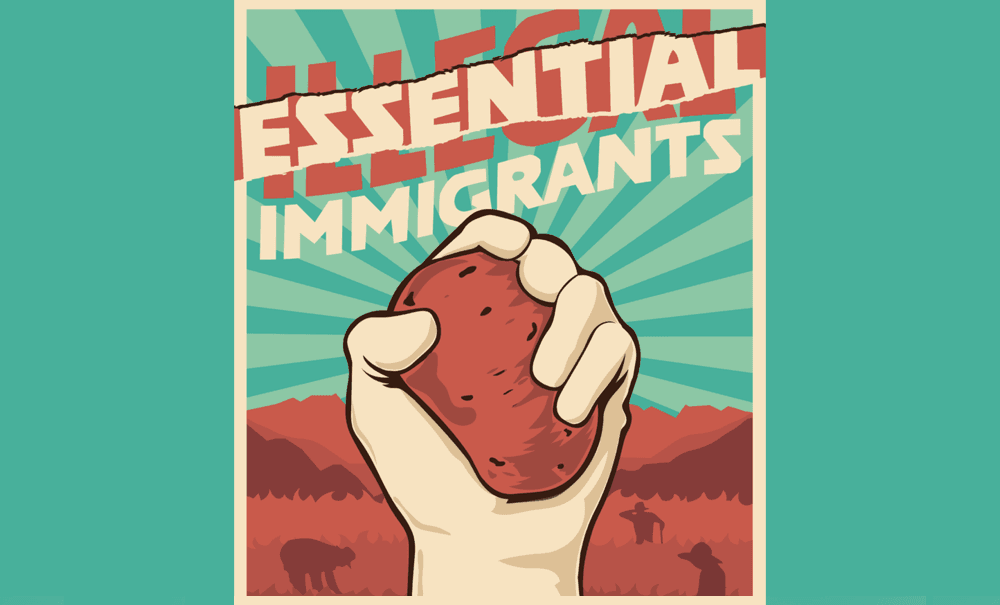

At the other end of the food supply chain—food production—immigrant workers face a new set of dangers during the crisis. With immigrants supplying 30-50% of the labor in the U.S. meat processing industry, Trump’s designation of the meat industry as ‘critical infrastructure’ during the pandemic means that his violently anti-immigrant regime has just acknowledged that thousands of immigrant workers are in fact “essential” workers. Since up to 50% of immigrant laborers in the meatpacking industry are undocumented, Trump’s pronouncement also acknowledges the critical, essential nature of undocumented labor in the U.S. (Note that a mere nine months ago, ICE conducted one of the largest workplace immigration raids in U.S. history at seven poultry plants in Mississippi, arresting nearly 700 hundred immigrant workers.)

Being designated an essential worker during this pandemic is hardly a blessing, despite popular celebrations of their “heroism.” For workers in the pork, beef, and poultry processing industries, becoming ‘essential’ often simply means that corporate employers can make more demands with fewer restrictions or protections. And when an essential workforce includes many undocumented workers, we have “created a workforce largely made up of people who aren’t legally allowed to work and also, now, not permitted to stop” (“The Workers are Being Sacrificed…” Mother Jones, May 1, 2020).

As meatpacking plants across the Midwest and South become hotspots for coronavirus infections, with confirmed cases at 214 plants, thousands of workers testing positive, and at least 59 workers dead, ’essential’ workers are revealed as ‘expendable’ workers. Many plants employ a wide diversity of immigrant workers from Mexico and Central America, Somalia, Sudan, and Burma. With the federal government demanding no interruption to the nation’s meat supply, and employers determined to keep their profits flowing, meatpacking plants are forcing their workforce to stay at grueling jobs, despite anxiety, shortages of PPE, illness and death. Refuse, and face losing both your job and unemployment benefits.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

Gratitude for your collective care in this ongoing moment of crisis and radical uncertainty. Together we will continue to build forms of solidarity and community action, as we fight for a future that embraces us all.

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network

Follow @JHSolidarity on facebook and twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.