Dear friends,

Against the sounds of deep summer, there is a distinct buzz as local immigrant justice groups return—with strength—to in-person activities. Adhikaar traveled to the White House, where member Rukmani Bhattarai joined a roundtable discussion with Vice President Kamala Harris, advocating a pathway to citizenship for TPS and DACA holders. This week, Desis Rising Up & Moving (DRUM) launches its six-week Summer Internship Program for South Asian and Indo-Caribbean youth organizers. And Make the Road NY will host the 10th Annual Trans-Latinx March on July 12, starting off from Corona Plaza, with a celebration of trans and queer visibility and a demand for TGNCIQ rights.

Our newsletter today is inspired by the work of a coalition of groups fighting for passage of the Dignity Not Detention Act in New York State. We highlight how recent the practice of immigrant mass detention actually is, and the urgent need to abolish this carceral response to migration.

Ending Mass Detention of Immigrants

“An economy based upon the confinement of people for profit is immoral and should be illegal.”

—Tania Mattos, Queens-based Policy and Northeast Monitoring Manager, Freedom for Immigrants

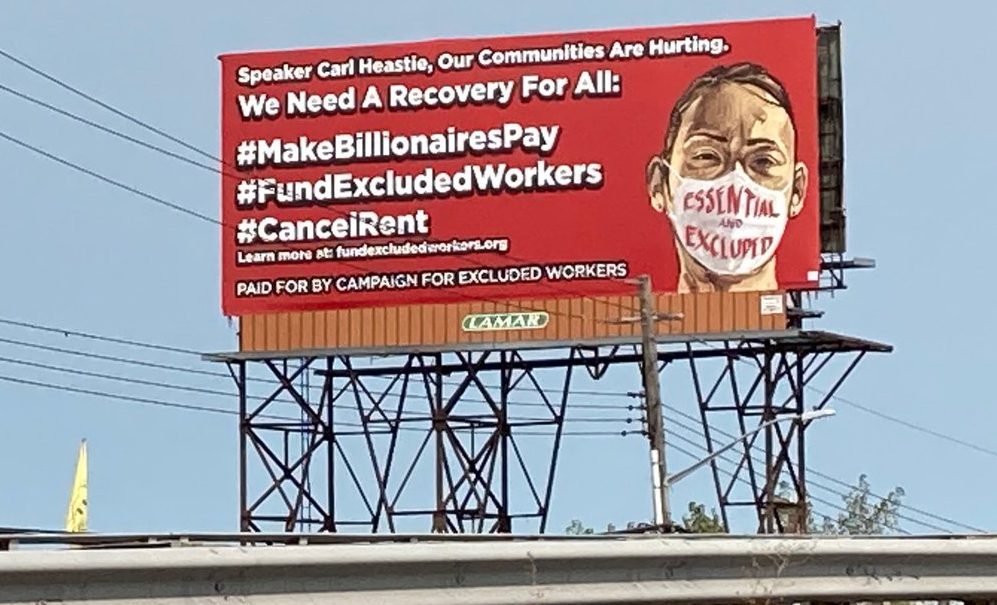

In 2017, when California passed the Dignity Not Detention Act, the co-sponsor of the legislation, Freedom for Immigrants, intended the law to become a model for other states. On May 17, 2021 a New York State bill with the same name was introduced, to end NY State’s existing and future immigration detention contracts with ICE or any private entity. Six other states have made similar calls for Dignity Not Detention, trying to loosen the hold incarceration economies have on local communities. When passed, the laws will end the federal practice of paying for the detention of immigrants facing deportation and instead allow them to remain with their families and communities.

During a recent visit to El Museo del Barrio, readers of our JHISN newsletter were struck by the collaborative work Torn Apart / Separados, a project that visualizes the financial influence of ICE. The project reveals ICE spending averaged $28 million a year in New York State over the past 7 years. The Mapping of US Immigration Detention Data shows the majority of ICE spending in NY State is for transportation costs; an 8th of transportation amounts were spent on translation services; half as much of translation amounts were spent on private security. Only after management, tactical & general supplies, and IT services, do medical spending costs feature—at a significantly lower amount.

Immigrant detention at a massive scale wasn’t always a US tradition. When detention began on Ellis Island in the 1890s, only 10% of arriving immigrants were held, most briefly for medical checks, fewer for longer security checks, and then released. When Ellis Island closed in 1954, Eisenhower made confinement the exception, replacing it with conditional parole, bonds, or supervision. Only in the 1980s, under Reagan, did mass detention practices begin. Initially a deterrent to Haitian refugees escaping the Duvalier regime, they were also applied to Cuban and Salvadoran refugees and soon became the standard practice. These practices paralleled ‘tough-on-crime’ laws that grew the detention economy and, fueled by anti-immigration political rhetoric, also coerced detainee labor in for-profit facilities.

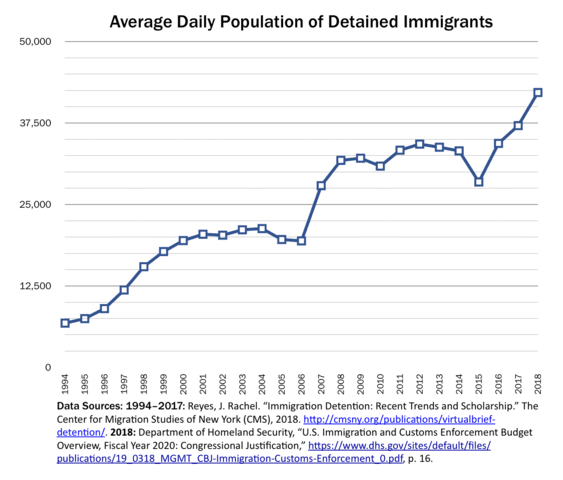

Congressional approval of DHS funding in 2009 required contracts with private detention facilities to include a minimum bed quota of 33,400 detention cells, to be paid whether used or not. Although Congress removed the Obama era’s minimum beds requirement in 2017, the number of guaranteed beds grew by 45% during the Trump administration because local contracts retained those guarantees and the count of immigrants in daily detention rose to over 50,000 by 2019.

Graph by Carwil

In 2013, facing a possible government shutdown, ICE released 2,000+ detainees to lower costs, and the Senate reprimanded it for violating the 2009 statute. DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano argued that detaining should be based on known threats not numbers of beds; data from ICE’s detention statistics reveal they considered only 17% of people detained to be a severe threat level, while almost two-thirds posed no threat level. The charge “aggravated felony” was created specifically for immigration law—as recently pointed out by Congresswoman Ocasio-Cortez, it describes offenses that are neither aggravated nor felonies. The language of “aggravated felony” is used to give the appearance of criminalized activity in our civil immigration process and minimize the ability to fight deportation and detention.

When the pandemic struck, authorities released thousands of detainees which, combined with guidance under the Biden administration, has dropped the daily detainee population reportedly to under 15,000. The reliance on detention-first policies meant ICE used more than $3 billion to fund the detention of nearly 170,000 immigrants in 2020 and still has ICE paying more than $1 million per day for empty beds.

The economics of detention are complex and significant – as outlined by Worth Rises – but should not drive the continuing detention of immigrants involved in civil immigration proceedings. Alternatives to Detention, ATDs, need to become priorities once again. Despite attempts by DHS to undermine their efficacy, ATDs can be 80% less expensive (under $5 per day instead of $130-$300 per day to detain an individual) and result in 90% compliance. In 2019, ICE received $184 million to develop an ATD called ISAP (Intensive Supervision Appearance Program) with over 95,000 participants. But ICE has implemented ISAP using for-profit private agencies that prioritize surveillance and onerous reporting requirements. Instead, advocates argue that ATDs succeed when trusted, community-based non-profits are involved.

When politicians submit bills like Dignity not Detention, or the ACLU calls for shutting down 39 facilities, or groups like Abolish ICE NY-NJ take actions to end ICE contracts in Hudson County, they expect detainees will be released to their families or local community. However, as we wait for Governor Murphy to sign a New Jersey law to prevent the renewal or development of new ICE contracts for detaining immigrants, the Biden administration is actually moving some detainees from NY and NJ to detention facilities as far away as Alabama, Louisiana, and Pennsylvania. The New York Immigrant Family Unity Project (NYIFUP) identified at least 22 detainees from New York who were moved to jails around the country, with unprecedented speed, in some cases without taking personal items including legal paperwork. They are further from their families, medical support treatments, and legal representatives.

Activists in NJ protested for 3 days at Senator Booker’s Newark office this week, demanding these transfers stop and everyone who was recently transferred be brought back to NJ so they can be released to their families. It is time to eliminate detention from US immigration procedures.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Attend the Releases Not Transfers Rally against ICE tomorrow at noon outside the Federal ICE Office in Newark (970 Broad Steeet).

- Sign the Detention Watch petition to close down 10 known problematic detention centers

- Join the Freedom for Immigrants Movement and share Miguel’s video Now, which features Freedom for Immigrants actions

- Join the Human Rights First Freedom for Detained Refugees Project

- Learn more about immigrant detention from the Supporting Immigrants online library of the Vera Institute of Justice

- Participate in Amnesty International’s Free People from ICE Detention Campaign

- Volunteer to Take Action with the Families Belong Together Movement whose works continues on after Trump

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.