Dear friends,

“We all must find a way to have the courage to get in trouble, to make good, necessary trouble,” John Lewis said. As we mourn his death this past week, we also bind his life and spirit to current struggles for racial justice. John Lewis faced down state violence and demanded voting rights for Black Americans. Today we honor his memory by collectively facing down state violence that is, again, armed and ready to make justice bleed. JHISN hopes that you might use the newsletter to make some good trouble this summer. Wherever you might be. Wherever it might be needed.

Newsletter highlights:

- Border Patrol’s Long History of Violence

- Who Counts? Protecting the 2020 Census

- Community Art-Making as Activism

1. First They Came for the Migrants…

The brutality that Customs and Border Patrol paramilitaries have unleashed on protesters in Portland is shocking, but perhaps not entirely surprising.

As I see white mothers and mayors being teargassed on the streets Portland, Ore., one word keeps bubbling up from my bleeding heart: “Welcome.” Welcome to the world of secret police and nighttime raids. The world where you can be snatched by an unidentified officer in an unmarked van. The world where you get to see an attorney, maybe, after the government is done beating you. Welcome to the world as experienced by brown people with foreign-sounding names in this country. —Elie Mystal (The Nation, July 2020)

CBP has made headlines in recent years for its openly racist brutality at the Mexican border; for casually separating children from their parents; for concentration camps where migrants are tortured in hieleras–“ice boxes”–and locked in cages filled with Covid-19. At least 111 people have died at the hands of the Border Patrol since 2010. But this is only the most recent chapter of a murderous history that goes back generations.

Established in 1924, during an earlier period of xenophobic frenzy, CBP became part of the new, sprawling Department of Homeland Security in 2002. It is one of the largest enforcement agencies in the world, fielding some 20,000 agents, with a budget of around $5 billion. By design, CBP has a loosely-defined mandate, which allows it to be used however the federal regime wants, including as a political police force.

Since its founding in the early 20th century, the U.S. Border Patrol has operated with near-complete impunity, arguably serving as the most politicized and abusive branch of federal law enforcement — even more so than the FBI during J. Edgar Hoover’s directorship. —Greg Grandin (The Intercept, January 2019)

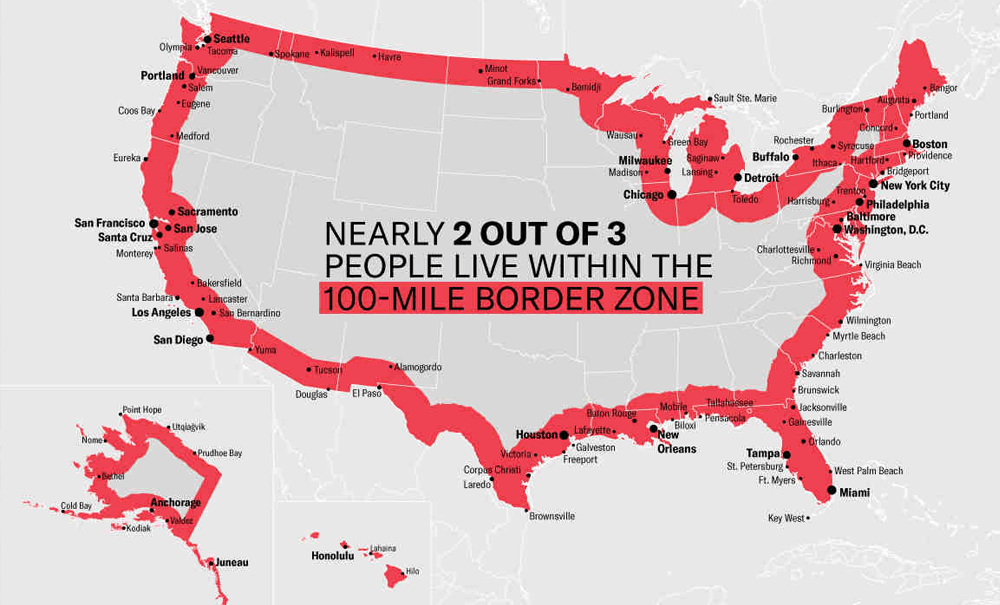

The Border Patrol operates outside clear borders, geographic or legal. Judges have affirmed that it can operate within 100 miles of any US border, including the coasts–a zone which encompasses 2 out of every 3 US residents. CBP has weaponized this bizarre definition of “the border” to establish intrusive checkpoints all over the country, to deploy “roving patrols” in sanctuary cities including New York, and to board trains and buses searching for people who “look undocumented.” (Protests by activists forced Greyhound Bus to deny CBP agents unrestricted access to the company’s buses last year.)

CBP’s mandate also has an international aspect. The Border Patrol Academy has trained counterinsurgency forces from a variety of overseas dictatorships. BORTAC, the paramilitary group leading the current repression in Portland, has been deployed in Iraq, Afghanistan, and throughout the Americas to carry out raids and beef up border forces.

Sometimes likened to an American SS, the Border Patrol has always welcomed white nationalists into its ranks, including Klansmen and neofascists. Beatings, rape, murder, racist abuse and sadistic torture have been common throughout Border Patrol history. In 2019, ProPublica exposed a secret Facebook group that had almost 9,500 Border Patrol members, including the current chief. Featuring endless racist jokes about migrant deaths, the group also mocked Democratic congresswomen–including AOC–who were investigating CBP abuses at the Mexican border. One poster encouraged agents to “throw a burrito at these bitches.” Thousands of abuse complaints have been lodged against CBP; these are routinely stonewalled and ignored.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Expand abolitionist demands to Abolish the Border Patrol, and Abolish the Department of Homeland Security

- Know our rights: https://www.acluaz.org/sites/default/files/field_documents/aclu_border_rights.pdf

- Refuse to collaborate: https://jhimmigrantsolidarity.org/how-to-not-be-brave

2. 2020 Census and Trump’s Attempts at Immigrant Exclusion

Last weekend marked the 15th year since four immigrant women founded Adhikaar and began serving as social justice advocates for Nepali-speaking workers in our neighborhood. The organization has grown and thrived; Adhikaar currently provides direct relief for those impacted by COVID-19, promotes health justice, pushes for worker safety, and campaigns for a Billionaires’ Tax. All while encouraging immigrants to complete the 2020 census.

Adhikaar has taken to the streets in Queens to educate the communities they serve about Congress’s constitutional responsibility to count all the people in the country every 10 years. To be counted is to take a stand against the fear-mongering used by Trump and his liegemen to dissuade people from participating in a process that determines congressional representation and appropriate distribution of federal resources. As Adhikaar, along with other local groups in the Queens Complete Count Committee, encourage immigrants to participate, the federal government is looking at other ways to discount them:

The Census Bureau has begun to examine and report on methodologies available to “provide information permitting the President…to carry out the policy” of “the exclusion of illegal aliens from the apportionment base”. —Steven Dillingham, Director of the Census Bureau, July 29, 2020

The 14th Amendment corrected the intentional racism of the original census charge, which excluded indigenous Americans and counted only three-fifths of all persons who were “not freemen or bound to service”. Trump’s push to eliminate immigrants from the census count was a nod back to the original wording in the Constitution; designed to redefine who counts as a person. The failed attempt to add a citizenship question to the census exacerbated an existing problem: historically, our national population has been undercounted, even more so in minority communities. People who fear that responding to the census might bring ICE or Border Patrol to their door are disincentivized to participate, as are historically marginalized groups who feel they do not benefit from the representation the census promises.

In September, the Census Bureau will send a seventh mailing, including a paper questionnaire, to people in the population tracts with the lowest response rates. There are many in Queens. Despite extending the census deadline due to the pandemic, we are not yet even close to the response rates in 2010. In 2010 the overall NYC response was 62%, a full 14 points below the national average. This year the national response rate is almost 63% while NYC is only at 54%. When we drill down into specific neighborhoods the differences are dramatic: East Elmhurst is only at 43%; in Corona, the majority of tracts are below 50% (and 10 tracts are under 40%), while in 2010 there were only 6 tracts which had responses under 50%. Although the rectangle between Roosevelt and Northern, from 76th to 86th streets, has a 68%+ response, all other areas of Jackson Heights average below 50%.

JHISN celebrates Adhikaar’s 15th birthday and honors their social media and text-banking outreach campaigns that have so far assisted over 4,300 people to complete the 2020 census. In the face of adversity and targeted exclusions, Adhikaar shows how to stand up and be counted.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Encourage people in your community to complete the census online.

- Sign up for local Census Outreach Phone Banking, through August 9.

- Educate yourself about the hard to count areas of our city and consider volunteering for a group working on census outreach in an area that you value.

- Retweet and like on facebook all the census outreach notices posted by Adhikaar.

3. Art as Activism

Art with organizing is all about building people’s power and finding strength in our communities; and art has always existed in our communities…that’s where our power lies.” —Mahira Raihan, Arts & Cultural Justice Organizer, DRUM

The power of art and the power of organizing are intimate allies. As hundreds of thousands of people in the US, night after night, filled neighborhood streets with cries for justice for George Floyd, new art-making also poured into our public spaces. From community murals and street art to the collective performance of thousands ‘taking a knee’ together, the mobilization of political power has been inseparable from an outpouring of creative work.

While the huge, bright yellow street paintings spelling out ‘Black Lives Matter’ in Washington DC, and in front of NYC’s Trump Tower, have received international attention, more community-driven BLM street paintings designed in lush colors by local artists have also proliferated in Jackson, MI, in Cincinnati, OH, in Charlotte, NC, and in Seattle, WA. Foley Square is the site of a gorgeous multicolored Black Lives Matter street painting collaboratively designed by multiple artists; the word ‘Black’ was designed by artist and immigrant Tijay Mohammed, using Ghanaian fabric motifs and imagery. In Harlem and Bed-Stuy, painting the street with Black Lives Matter was a community event, with hundreds of local residents participating.

Desis Rising Up and Moving (DRUM) here in Queens is currently running a two-month Art to Activism program, mobilizing South Asian and Indo-Caribbean working-class youth to collaborate on a community-based art project. Aimed at deepening understandings of both police brutality and anti-blackness in South Asian-American communities, the project uses art-making as a catalyst to social change. Art to Activism builds on DRUM’s earlier Moving Art—Making Art for Our Movements program which created collective art “grounded in our communities’ experiences and dreams of liberation.” Visual art, theater, ‘zine-making, and poetry are all a regular part of DRUM’s organizing and cultural work.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Support DRUM’s Building Power & Safety through Solidarity campaign.

- Purchase a copy of DRUM’s ‘zine created collectively in the Moving Art program.

- Visit the Black Lives Matter street art in Harlem, Bed-Stuy, and Foley Square!

- Work and play with local artists, neighbors, kids, and friends to design street art for immigrant justice on 34th Ave Open Streets.

Gratitude for your collective care in this moment of sustained and multiplying crises. Together we will continue to take strength from our solidarities, and our histories of creative resistance.

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.