Dear friends,

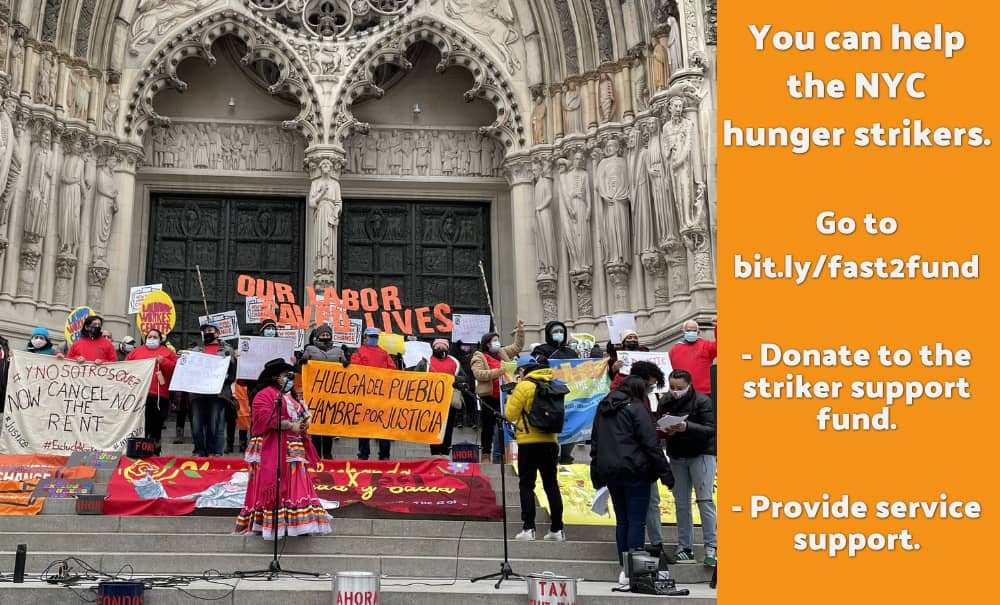

Since we sent our last newsletter two weeks ago, immigrant workers have continued their hunger strike demanding inclusion of a Fund for Excluded Workers in the New York state budget. The ‘Fast for the Forgotten’ has brought together workers, mothers, aunties, brothers, husbands, sisters, grandmas, elders, and our neighbors, who are putting their bodies on the line to get emergency pandemic relief for undocumented workers. We continue to cover the historic strike below.

We also report on a recent legislative victory celebrated by local immigrant justice groups. House passage of the American Dream and Promise Act 2021 is a major step toward creating a possible citizenship path for Dreamers, TPS holders, and other immigrant residents.

Newsletter highlights:

- ‘Fast for the Forgotten’ enters its third week

- Legislation promises citizenship path for over 4 million immigrants

1. Hunger strike continues as state budget talks drag on

“We are here because we have suffered enough. We have already endured a year of hunger. What difference does it make to endure two or three weeks more with the purpose of getting something that we deserve…Our stomachs ask for food, but our hearts ask for justice.” —Veronica Leal, hunger striker (Documented, March 31, 2021)

Now in its third week, with individual hunger strikers in wheelchairs and facing increasing health risks, the ‘Fast for the Forgotten’ is a challenge now for us. What will we do, as immigrant and undocumented workers refuse to end their strike until the New York State legislature passes a ‘just budget’? How to measure our own hunger for justice against the ease of forgetting that almost a quarter-million undocumented immigrants in New York State have been excluded for over a year from any federal pandemic emergency relief? What does it mean to remember that many of the workers who have stocked grocery shelves, delivered take-out food, served meals and washed dishes for folks who venture out to eat, are hungry? And have families and children who are hungry too.

The #FundExcludedWorkers coalition, led by immigrant New Yorkers, has been mobilizing political pressure since last summer to tax the rich and raise state revenue to financially protect undocumented workers devastated by the pandemic. On March 16, as JHISN reported, the coalition launched a hunger strike now in its 19th day, with immigrant strikers staying in Judson Church in the West Village, and dozens more participating statewide in the strike in Westchester, Syracuse, and Albany. They aim to secure a $3.5 billion workers fund in the New York State budget. The initial proposed budget contained a suggested $2.1 billion fund, but activists insist that anything less than the full $3.5 billion is not enough to retroactively make up for the lost emergency support to excluded workers over the past year.

The state budget was scheduled to be finalized by March 31. But that deadline has come and gone, with negotiations dragging on through this weekend. Hunger strikers continue to drink water and refuse food. Day 20…21…22?

Since the launch, elected officials and NYC mayoral candidates have joined the hunger strike on select days; immigrant justice groups and their allies have organized virtual hunger strikes in solidarity; rallies have been held in front of Governor Cuomo’s office; supporters have been arrested for civil disobedience in the streets; local politicians have washed the feet of hunger strikers in a symbolic Holy Thursday action; and musicians, dancers, artists, and storytellers have put their creativity in service of funding excluded workers.

How has Governor Cuomo responded to this historic mobilization? By March 29, Cuomo’s team had introduced new barriers to workers’ ability to access the multi-billion-dollar fund included in the state assembly’s original budget proposal. The ‘poison pills’ proposed by Cuomo would require immigrant workers to present federal ITIN numbers, or bank account and payroll stubs, in order to access funding. “We cannot move forward with an Excluded Workers Fund that excludes the excluded workers,” noted Jessica Maxwell of the Central New York Workers Center. Immigrant workers and their allies rallied in Washington Square Park to decry the new barriers and demand a ‘flexible application’ process for undocumented workers. If Cuomo’s restrictions are put in place, most of the individual hunger strikers will not be eligible for the funds they starved for.

As we remember the ‘Fast for the Forgotten’ and the urgent need for government support of all workers caught in the pandemic catastrophe, the words of Ana Ramirez—a hunger striker speaking at a public rally on Day 5—can inspire and haunt us:

“I want to make it clear to this nation, the most important nation in the world, that we will no longer conform to being told ‘Good Job.’ We want the laws to be just, because it is then that we can work with love, with honor, with dignity…

“It is not just me but thousands of families—families that went to the bakery to bake the bread so that the rich can eat during this pandemic comfortably. I am forgotten, I am one of the excluded. We are house cleaners, construction workers, restaurant workers, retail workers, laundry workers, all of whom have worked hard for this nation…

“When the body is depleted of its minerals, the vitamins that it needs, you begin to tremble. But this gives me more strength. Because that is the hunger that thousands of working families face…

“And the rich, the powerful, the thieves that don’t pay taxes, they were able to go through the pandemic with comfort and ease. But we the poor don’t ask for anything given.

“I want to tell you all that my hunger strike is only beginning. Because if they want to see me die of hunger, they will.”

—Ana Ramirez, hunger striker since Day 1

(translated from Spanish)

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Immediately contact your state legislators to voice support for the $3.5 billion Excluded Workers Fund.

- Follow daily Hunger Strike updates, solidarity events, and social media campaigns at Fund Excluded Workers website and Instagram.

- Check out the Allies Action Toolkit with instructions on how to organize your own solidarity hunger strike, and amplify via social media.

- Donate to the Strike Support fund here.

2. Path to citizenship could open for millions

“Yesterday, yet again, we made history with the passage of the Dream and Promise Act (H.R. 6). This legislation, which passed with bipartisan support yesterday by a vote of 228-197, is a historic step towards correcting the injustices in America’s immigration system. … This is truly a grassroots win.” —Pabitra Khati Benjamin, Adhikaar (email, March 19, 2021)

More than 4 million undocumented immigrants could get a path to citizenship under a bill passed last month by the U.S. House of Representatives.

While it faces a potentially steep uphill climb in the Senate—and it would leave millions of other people still without a path to legal status—the new bill has been supported by many immigrant advocacy groups, including Queens-based Adhikaar.

The American Dream and Promise Act of 2021 would provide conditional permanent residence for up to 10 years to people who came to the United States as children, including recipients of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals). By meeting certain requirements—for example, going to school or getting a job—those individuals could then gain permanent resident status (a green card), which could eventually lead to citizenship.

They’d be ineligible for conditional status if they have certain criminal offenses on their records, and they’d lose their status if convicted of a serious crime. Additionally, the Department of Homeland Security would have authority to deny applications if officials have “clear and convincing evidence” that the applicant was involved in gang activity in recent years or is otherwise a public safety threat. These provisions have been criticized by several groups, including The Bronx Defenders and Human Rights Watch, who cite the disproportionate effect the stipulations could have on immigrants of color.

Certain other immigrants, including those with Temporary Protected Status and those protected under a program called Deferred Enforced Departure, would also be eligible for permanent status under the new bill.

The Migration Policy Institute estimates that about 4.4 million of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the United States could become eligible for permanent status if this bill becomes law.

“The passage of the American Dream and Promise Act within the first 100 days of the 117th Congress signals the overwhelming support for the legislation and a commitment to make good on overdue promises,” Amaha Kassa, executive director of African Communities Together, said in a statement. “We call on the Senate to take up and swiftly pass this legislation into law.” President Joe Biden has already voiced his support for the bill.

The so-called Dreamers—young people who were brought to the United States as children, many of whom have been protected by DACA—are probably the most often discussed group that would be covered by the bill. Less often talked about are TPS holders.

Temporary Protected Status grants temporary legal status to immigrants who would face humanitarian emergencies like war or fallout from natural disasters if sent back to their home countries. (Deferred Enforced Departure, which currently covers people from Liberia and Venezuela, is similar to Temporary Protected Status, and DED holders are also covered by the new bill. But whereas DED is at the discretion of the president, TPS is under the supervision of the secretary of Homeland Security.)

Nepal, Syria, Haiti, and Somalia are among the countries whose citizens have gained TPS protection in the United States.

“TPS holders are critical essential workers on the frontline of our economic recovery from the ongoing COVID-19 crisis,” said Pabitra Khati Benjamin, executive director of Adhikaar. The group advocates for the rights of the Nepali-speaking community here in Central Queens and has been a leader in the fight to maintain protection for TPS holders. (Nepal received TPS designation after the massive earthquake and aftershocks that hit the country in 2015.)

The Trump administration tried to rescind TPS protection for hundreds of thousands of immigrants from several countries, including Nepal, but the policy was stalled amid litigation over the issue, which is still pending. Adhikaar has called for the Biden administration to redesignate Nepal as a protected country. At the same time, the group has advocated for Congress to provide permanent residency to TPS holders.

If passed into law, the new bill would be a significant step in that direction. It wouldn’t create the pathway to citizenship for all undocumented individuals that Adhikaar and other groups want, but advocates say this is still a victory.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- If you are able, consider a donation to Adhikaar to support their ongoing fight for Nepali-speaking TPS holders.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.