Dear Friends,

As a smothering blanket of white nationalism and authoritarianism descends over the US, sanctuary cities are a crucial line of defense against the regime’s plans for mass deportation. In our last newsletter, we saw that many US cities are reaffirming their sanctuary city status in defiance of ICE threats. Today’s newsletter adopts the definition of “sanctuary city” as “a collection of policies and political will” and discusses Mayor Adams’ corrupt betrayal of NYC’s promise of sanctuary.

Our second article introduces you to TRAC (Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse). We explain how this unique and valuable tool has provided public access to data from various federal government agencies and explore its current transformation.

1. Adams Attack on Sanctuary Causes Fear and Confusion

“I think Mayor Adams does not know his own city or does not care to know his own city. The people who pay taxes in his city. The people who go out and shop every morning. The people who are up at 4 a.m. driving deliveries. Those are the people who run this city and are being served up on a silver platter for President Trump.” –Carina Kaufman-Gutierrez, Street Vendor Project

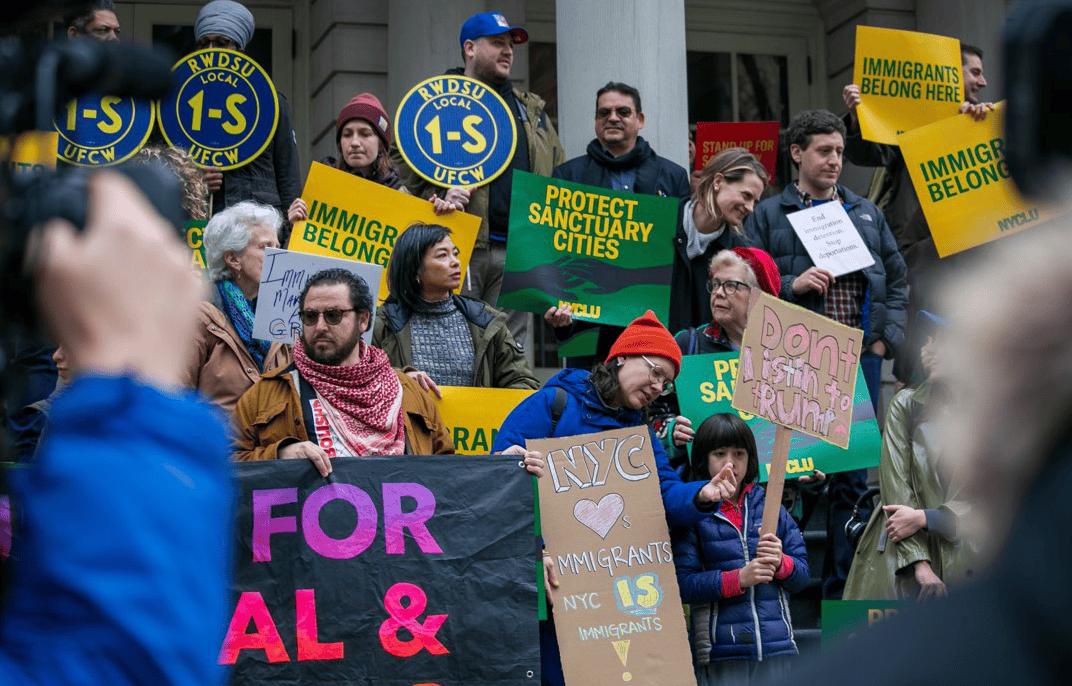

The term “sanctuary” evokes mental images of families sheltering from ICE in church basements or private homes. For instance, during the first Trump administration, Aura Hernandez and her children, fleeing violence in Guatemala, lived inside the Fourth Universalist Society in Manhattan for almost a year, successfully holding off ICE attempts to deport them. Today, churches are quietly discussing their options for similar actions.

But what is a “sanctuary city”? After all, we can’t put walls around NYC. As a November article in The City explains, “‘sanctuary city’ isn’t really a hard-and-fast legal edict. It’s more of a collection of policies, combined with political will, that guide how local and federal authorities [such as ICE] interact.”

In practice, this includes guaranteeing legal rights and access to public services for all residents, whatever their immigration status. It often involves outlawing immigrant detention centers. Of critical importance today, it usually means refusing to help ICE deport people in city facilities like schools, jails, courts, and hospitals unless they have a warrant signed by a judge.

But in NYC, both political will and policies are under attack from right-wing forces and the Adams administration. While undocumented immigrants were hailed as heroic “essential workers” only a few years ago, they are now endangered because of a failure of solidarity, manufactured confusion, and the mayor’s craven and self-serving accommodation with the Trump regime’s plan for mass deportation.

Adams has claimed on many occasions that he upholds New York’s sanctuary city status. But since Trump’s reelection, the mayor has turned sanctuary into a bargaining chip, cynically offering up the city’s 400,000 undocumented immigrants as a potential sacrifice to get himself out from under federal corruption charges. In December, he declared, falsely, that immigrants accused of crimes were not eligible for due process under the Constitution. He floated the idea of using executive orders to get around current sanctuary laws and help ICE arrest more immigrants.

On February 10, a federal Justice Department memo announced that serious criminal charges against Adams would be suspended—not because they lacked merit, but because they might supposedly interfere with Adams’ ability to fight crime and “illegal immigration.” On February 14, Adams and Trump “border czar” Tom Homan appeared on “Fox and Friends” to celebrate their new collaboration. A visibly perspiring Adams, laughing nervously, told Homan, “I want ICE to deliver.” Homan, for his part, told the Fox audience that “If he [Adams] doesn’t come through, I’ll be back in New York City and we won’t be sitting on the couch, I’ll be in his office, up his butt, saying, ‘Where the hell is this agreement we came to?”

During a partisan Capitol Hill hearing designed to attack sanctuary city mayors earlier this week, anti-immigrant Republicans treated Adams with kid gloves. House Oversight Committee Chair James Comer even praised him for his willingness to work with ICE. It was Democrats who challenged Adams, denouncing his collaboration with Homan.

Even before Trump’s February 16th executive order to open up sensitive areas like churches and schools to deportation raids, the Adams administration was pushing city agencies to loosen sanctuary city protections and to cooperate with ICE. Instead of instructing city employees to follow sanctuary policy, keeping ICE out unless they showed a legal warrant, Adams directed that “if you reasonably feel threatened or fear for your safety, you should give the officer the information they have asked for or let them enter the site.” This is widely viewed as undermining the intent of sanctuary city legislation. Since then, the mayor has promised to “coordinate” with ICE on deportations.

Immigrant advocates are proactively organizing on several fronts against what they see as an ominous weakening of the spirit and letter of sanctuary city provisions. On February 6, state Sen. Zellnor Myrie and other Democrats held a news conference outside Kings County Hospital to protest a memo from NYC Health + Hospitals that warned workers not to help patients avoid ICE. Other hospitals have circulated similar memos, causing widespread controversy and anxiety among patients, employees and immigrant communities.

Immigration activists are also trying to stop the reopening of an ICE outpost at Rikers Island, which was closed down in 2015 as a result of sanctuary city legislation. The ICE facility was using fingerprints and other jail data to deport many prisoners awaiting trial. This kind of synergy between prison systems and ICE contributed to a surge of deportations under the Obama administration. Adams now hopes to use an “executive order” of dubious legality to restore the Rikers ICE station.

On February 9, in the wake of reports that immigrant families are keeping their children home due to worries about ICE in the schools, Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos released a video to reassure parents. “As always, non-local law enforcement is not permitted in any of our school buildings without a judicial warrant or unless there are exigent circumstances,” she said. However, given Adams’ support for ICE, Make The Road Action’s Manuel Ordonez found Aviles-Ramon’s words less than comforting. “It’s impossible that my community is going through this difficult time, that they can’t even go to church, they can’t take their kids to school, they can’t shop at supermarkets because of fear of being arrested and deported.”

To the best of our knowledge, mass ICE raids have not yet occurred in NYC schools, hospitals, courthouses or churches. But activists are concerned that Adams is helping Trump to lay the groundwork: criminalizing immigrants, cheerleading ICE, releasing memos and executive orders that challenge sanctuary laws, and generally stoking fear. “This mayor has been running amok in this city for too long, all for his own self interest,” says Murad Awawdeh, president and CEO of the New York Immigration Coalition. “He’s enabling Trump’s mass deportation machine by sowing confusion.”

What Can We Do?

- Join the campaign for the New York for All Act.

- Know your rights when facing ICE, and help others know them too.

2. The Return of Vital Immigration Data

On January 8, 2025, a critical and unique reporting tool, which JHISN has often used for reliable data reports about US immigration, abruptly went silent. The esoterically named Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) was established in 1989 by Susan Long and the late David Burnham. As Director of the Center for Tax Studies at Syracuse University (SU), Susan had leveraged the 1966 Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) to gather Internal Revenue Service data for her work and dissertation. David was an investigative reporter of some renown. She was into numbers, and he was into words. They both advocated for public access to information and so, together, established TRAC with its purpose of “providing the American people with comprehensive information about staffing, spending, and enforcement activities of the federal government.”

David and Sue created a FOIA model for gathering data from non-cooperative federal organizations that would simply claim they did not have the information to share. Their TRAC process begins with a FOIA demand for available metadata about the topic of their research. After analysing the documents from that demand, they initiate further FOIA requests for the data disclosed by the initial metadata. The final step of their process uses data analysis to produce validated reports for general consumption. This makes it possible for us to discover, for example, that at this same time last year, over 600 people at the Genesse detention facility in New York state had been detained by ICE for one to two years.

50% of TRAC staff time is spent on FOIA requests, and each request is lengthy. A recent settlement for immigration data took 20 years. They currently have three FOIA lawsuits against ICE, initiated in 2010. ICE challenged those requests by simply asserting that the immigration data was exempt from disclosure. The courts ruled in TRAC’s favor. This FOIA work is conducted by pro-bono lawyers, often from the Public Citizen Legislation Group, a public interest law firm litigating cases at all levels of the federal and state judiciaries. The work of Public Citizen primarily involves consumer health & safety and consumer financial protection, overseen by the federal agencies that Elon Musk’s Dept of Government Efficiency recently decimated based on the recommendation of Project 2025.

Over the past 35 years, TRAC has produced a huge trove of data describing US immigration, Judges, and the federal agencies of the ATF, DEA, FBI, and the IRS. They also have a TracPlus report revealing data about civil rights, Social Security, and the environment. Perhaps surprisingly, Federal organizations have relied on TRAC reporting data for internal use. They do this through a subscription model that allows organizations, news media, and lawyers to access the data compilations. The Federal Reserve board once held a subscription because the TRAC reporting was more accessible than any internal systems. Immigration departments also have subscriptions because they have to give criminal enforcement data to prosecutors, and TRAC provides that data.

Sue points out that, although organizations may use TRAC data to assist in policy advocacy, TRAC itself is NOT a policy group: TRAC is focused on data availability. Since 1999, SU had hosted the TRAC database and reports on its website. Developing a new website with a better user experience was something Sue and David had been discussing over the last decade. However, the transition to the new tracreports.org site was fast-tracked in January. According to The Houston Chronicle, there had been a “sometimes testy internal [university] dispute” over the last two years, resulting in the recent deletion of the entire TRAC archive from the SU website. The university maintains there has been no external pressure to take down the TRAC site, however, the removal came at an inopportune time, just as the anti-immigrant Trump administration was about to return to power.

The new website TRAC launched last month allows them to provide more effective access to data. For example, their new Quick Facts on Immigration reveals that over 50% of those held in ICE detention have no criminal record. They are still working to reestablish access to ALL the data that once lived on the SU website, but are currently prioritizing the release of key information.

In addition to immigration data reporting, the TRAC website includes access to a substantial and always growing Reference Library of Government Studies on Immigration. The team has also been sending data to people who made specific requests for information that is not yet back online. In fact, the TRAC team had no sense of how broadly their data was in use until they started receiving emails from around the world, including from JHISN, asking what happened and if and when the website would be back online.

Before 2015, the work of TRAC had been recognized by the Electronic Frontier Foundation as well as the FOIA Project. Since that time, David and Susan had discussed how the TRAC system could continue after they are no longer around, a question that has gained urgency following David’s passing last year. They had established TRAC as a non-profit organization so that it, not they, and not SU, owned the data. They have seen thriving non-profits fail after the founding leader retired, and they both knew that the co-directorship that worked so well for them may not be the way for future leadership. Sue is certain that much of TRAC’s future will rely on volunteer support, and she is actively seeking and inviting discussion from others with solid ideas as to what the next stage in TRAC’s life will look like and determining how that future can be led.

What Can We Do?

- Send an email to trac@syr.edu if you believe you have skills you can volunteer to help them with their current and future work.

- Become a Member of Public Citizen or donate to support their work.

- Discover how NYU’s Gumshoex AI project is helping search the thousands of FOIA requests stored in Muckrock (which features TRAC’s work) and examine the projects and requests that Muckrock already has on immigration.

- In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.