Dear friends,

We reach out to you, again, in hopes that we might find new ways to connect even as our daily lives remain physically distanced from each other. Collective care feels urgent and particularly difficult now. Some of us woke up to the latest news about the unfolding tragedy in central Queens–Jackson Heights, Elmhurst, Corona. Our home.

The coronavirus, here as elsewhere, both reflects and deepens long-standing economic and racial inequalities. And the vibrant immigrant communities that are the life-blood of Jackson Heights are being decimated. We must join forces any way we can, collectively, with love and creativity.

Newsletter highlights:

- A look at the central role of immigrant labor in our healthcare infrastructure and in the battle to save lives during the COVID-19 crisis.

- The grassroots work of Queens Neighborhood United (QNU) during the pandemic, making visible the most vulnerable among us.

- An invitation to invent ways to sustain public memory and honor the neighborhood people being lost to the pandemic.

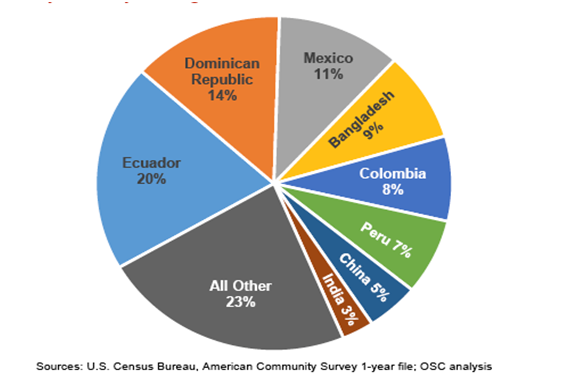

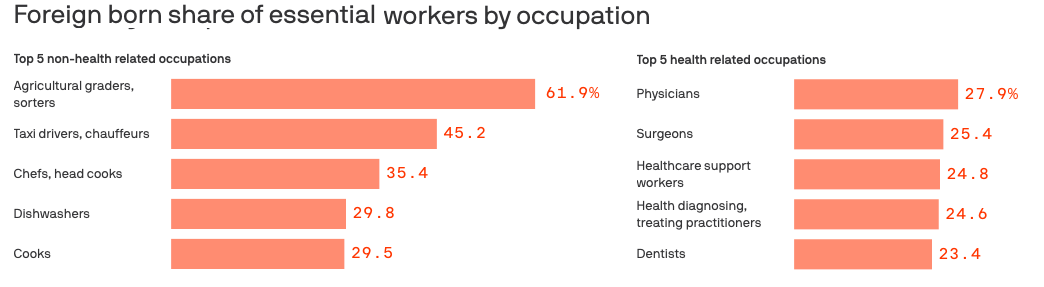

1. Healthcare workers and essential workers are immigrant workers

As we search for practices of solidarity in a global pandemic, our support for healthcare workers becomes especially important. Solidarity with healthcare workers is solidarity with immigrants. While the US healthcare system teeters on the edge of an almost unimaginable disaster, immigrant healthcare workers are doing their best to keep it from collapsing completely. As COVID-19 spreads through the US and the government closes its borders to non-US citizens, nearly 1.7 million foreign-born medical and healthcare workers are on the frontlines of the national crisis, according to the Census Bureau.

Source: Axios Health Apr 3, 2020

All told, about 25% of all US healthcare workers, and almost one-third of US doctors, are immigrants. Twenty-nine percent of nurses in the New York/New Jersey area are immigrants. Even the Trump administration has realized that the US needs this workforce right now:

Since it came to power, the Trump administration has waged a relentless, multi-layered war on immigration. But it only took a few days of panic over the spread of the novel coronavirus for the government to start seeing the value of at least some immigrant workers. In an announcement published on March 26, and promoted on its social media channels, the State Department called on foreign medical professionals who already have US visas to either move forward with their plans to come work in the country or, if they are already in the country, to extend their stay. Source: Quartz March 30, 2020

Nevertheless, incredibly, some 29,000 frontline medical workers who live under the tenuous protection of the DACA program (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals), are facing the possibility of immediate deportation. The Trump regime has gone to the Supreme Court for final authorization to destroy this Obama-era program. Analysts say that the Court will probably side with the regime. Not much has changed since last November when Ian Millhiser wrote, “The fate of DACA and the approximately 670,000 immigrants who depend on DACA…appears grim.” The blow could come literally any day now.

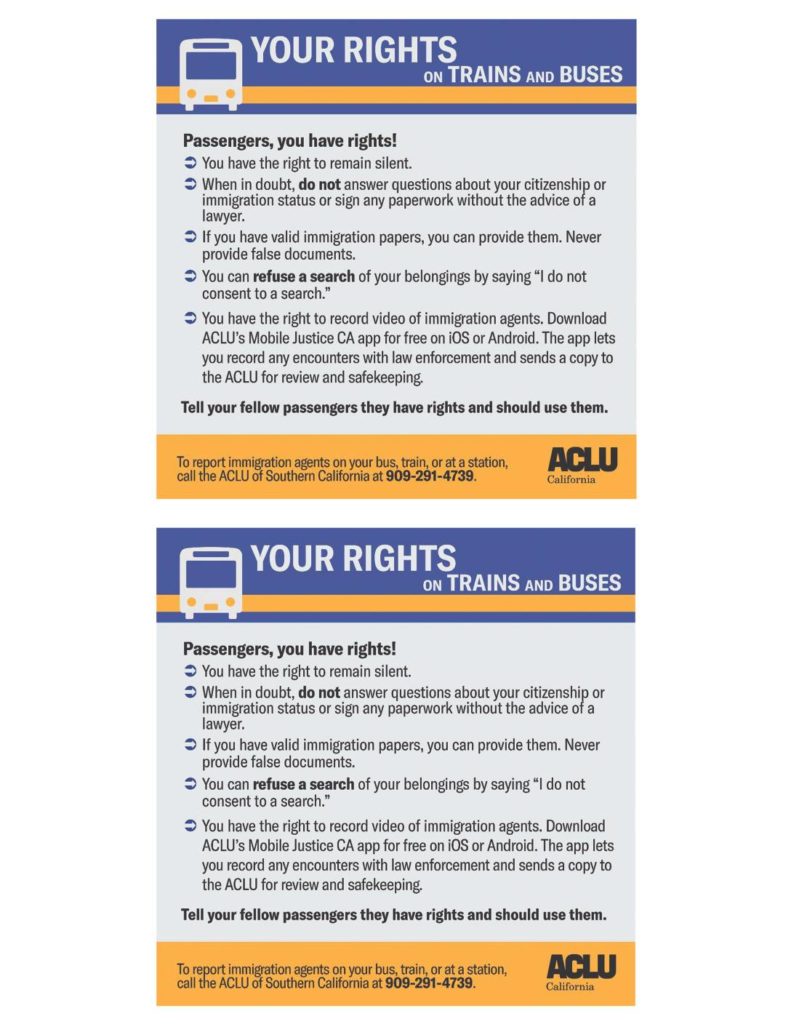

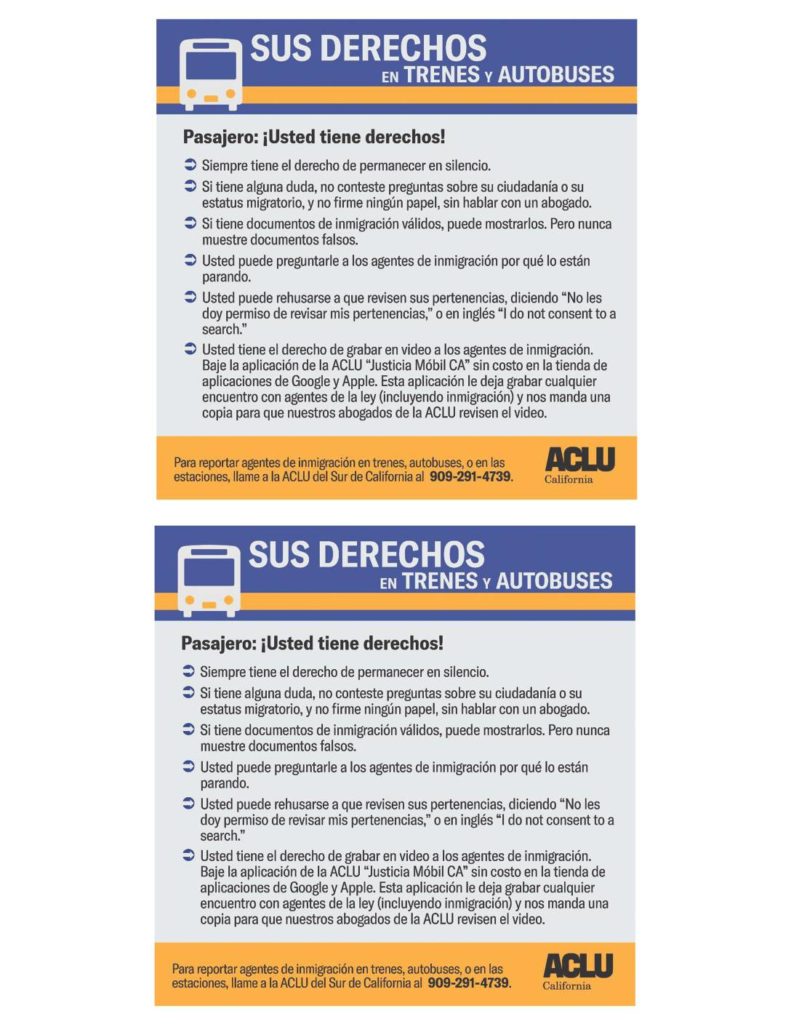

Will we see ICE agents dragging health care workers out of Elmhurst Hospital in the middle of the pandemic? Or, as an op-ed in the New York Times speculates, will immigrant workers “be asked to serve in this crisis for now, only to be deported later”?

Meanwhile, Dr. Chen Hu, an Asian-American physician at NYU Langone Medical Center, describes what it feels like to be both “celebrated and villainized” during the pandemic: celebrated for his life-saving work for COVID-19 patients; villainized as a second-generation immigrant of Asian descent who is harassed on the subway as he heads to work in his blue medical scrubs.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

- At 7 pm each night, join your Jackson Heights neighbors by coming to your window to celebrate our amazing healthcare workers with cheers, applause, and pots ‘n pans!

- Check out the work of Queens Feeds Hospitals. Local restaurants like The Queensboro and Senso Unico are closed, but they are taking donations and providing good meals to Elmhurst hospital workers.

- Support the multi-pronged efforts to get personal protective equipment (PPE) to health workers

- Join the #GetThemPPE hashtag campaign on Twitter

- Sign and circulate the petition by the NY State Nurses Association demanding the Defense Production Act be put to full use for the mass production of PPE, COVID-19 tests, and other much-needed medical equipment.

- Sign and circulate frontlineppenow’s change.org petition to urge our government, industry, media and the general population, to assist HCWs in obtaining immediate access to critical PPE

- If you are a health care worker, please consider sharing your story about the lack of PPE with Frontline PPE Now.

2. Fighting Criminalization and Displacement with Queens Neighborhood United

Queens Neighborhood United (QNU) is a diverse, community-based organization founded in 2014 to address local issues including policing, immigration, community control of public land, and the growing economic displacement of small local stores by large chains (like Target).

Last weekend, QNU shared news with their 3,500 Facebook followers of police arresting three homeless people in Corona Plaza with no explanation. This action flies in the face of the CDC guidance, as reported by The Intercept: “Unless individual housing units are available, do not clear encampments during community spread of COVID-19.” Putting homeless people in jail, where physical distancing cannot be practiced, directly exposes them to the threat of contracting COVID-19. QNU reminds us that the CDC and WHO repeatedly state that “jails and prisons are extremely dangerous during a pandemic.”

QNU exemplifies another important aspect of true community support in a pandemic: Mutual Aid, a concept many people are becoming familiar with and mistakenly think of as some form of charity. The truth is that the best people to trust to organize Mutual Aid are the already existing grassroots groups, like QNU, who have been doing this work for many years. They have proven their leadership, advocating for the people in their neighborhoods with actions such as Rent Strikes. And they make community services available to the people who actually need them. These are the organizations that can best guide us in how and where to give our financial support during the crisis, because they are already trusted by and embedded within our communities.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

These are the groups that QNU has identified as great to directly support. You don’t need to donate to every group (unless of course, you can), but pick at the one that resonates with you personally…and then ask your friends to do the same! Your network will help their network.

- If you hear about an organized rent strike, support it in every way you can.

- Contribute to New York State Youth Leadership Council emergency fund for undocumented youth and their families.

- Do these 5 things to support food workers.

- Support the Street Vendor Project.

- In Memory of activist Lorena Borjas, Donate to the Transgender Emergency Fund.

- Help reach the $25,000 goal to provide food and medicine to the Laundry Workers Center.

- Help Vinylbomb make personal protective equipment for our medical personnel.

3. In Memoriam

Make the Road’s Trans Immigrant Project has been posting “Rest In Power” memorials for the trans activists in our neighborhood lost to COVID-19. The names of Jamilet Valente, Lorena Borjas, Liz Fontanez, and Yimel Alvarado may not be known to us in the same way as rich personalities who post on social media about their fun ways of dealing with social distancing at home, but they have had significant influence in our neighborhood. These activist women helped combat the ostracism and exclusions that transpeople suffered long before the current health crisis and the government is not to be relied upon to help replace these leaders and their programs with the emergency funding they will need to continue their work.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

- JHISN is looking for a creative way for everyone in our community to share the loss of friends, neighbors, and family in the pandemic and to do it in a way that is not as fleeting as social media. After 9/11 the posters of loved ones were seen throughout the city. But with shelter-at-home requirements, we cannot go out and pay homage the same way. Help us build an online solution that allows us to share our grief and memorialize those we mourn. Contact aniotus@outlook.com if you have ideas or want to help.

We wish everyone protection, safety, and well-being. Thank you for continuing to protect our wider and deeper home, in communities of care and solidarity.

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network