Dear Friends,

As the national count of coronavirus victims reaches more than 100,000, as Corona and Elmhurst continue to experience some of the highest hospitalization rates in NYC, we wonder when grief will have an end. With corporate media focused on ‘reopenings’ and the ‘mask wars,’ we want to use the newsletter to keep our focus on the local, the possible, and the unfolding realities around us. Both the grim and the hopeful.

A reminder that on June 1, Art from the Epicenter, a Jackson Heights-based artists’ initiative to raise money for local mutual aid groups, begins its Instagram auction of donated artworks. The auction runs June 1-10, and we encourage all of you who are financially able to participate!

Newsletter highlights:

- Public Charge, Part 1: Intended to Exclude

- Protesting during a Pandemic

- New Report on COVID-19 Crisis among Immigrant New Yorkers

1. Public Charge (Part 1 of 3)

The public charge rule was designed on purpose to be confusing, complicated, and scary. You have rights in this country no matter where you were born. The more we know about our rights, the harder it is for the Trump administration to scare us. We encourage you to learn more about your situation before making decisions that may harm you or your family. (National Immigrant Law Center)

One of the ugliest attacks the Trump regime has launched against immigrants is a set of new “public charge” regulations. The new rules are meant to keep poor, mainly non-white immigrants out of the US, and to sow fear and confusion among those who are already here, discouraging people from getting permanent residency as well as the social benefits they are entitled to. The long-term goal of the administration is nothing less than a massive distortion of the US immigration system, skewing it to welcome the wealthy and exclude the working class.

“Public charge” first became law as part of the Immigration Act of 1882. The Act mandated the exclusion of any immigrant “unable to take care of him or herself.” The government’s interpretation of this vague phrase has evolved, often reflecting waves of racial and class chauvinism. In the twentieth century, public charge rules were used “first to keep out poor Asian Indians and Mexicans and then to keep out poor people generally.” (Daniels and Graham, 2001) In the 1930’s Jews fleeing Nazi Germany were kept out of the US by public charge tests.

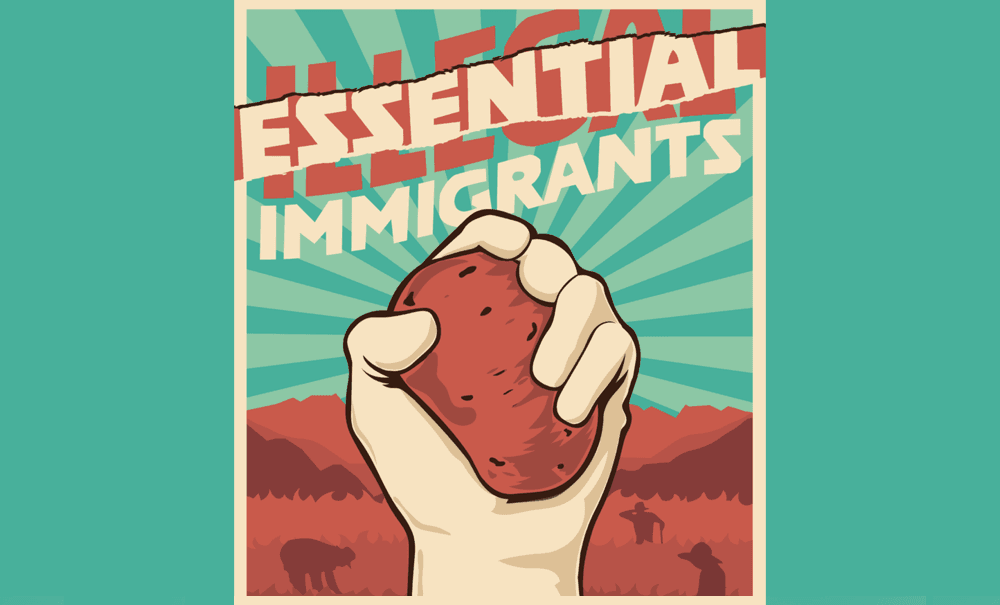

Public charge regulation is rooted in a xenophobic narrative that portrays immigrants as a drain on the economy. This has been widely debunked. Study after study shows that immigrants provide an overall boost to the economy. They pay billions in taxes, have enormous spending power, and “end up contributing more money into the economy than they take out in public services” (“US Immigrants Pay Billions..” Quartz)

In recent decades, the US generally raised public charge issues only against immigrants who were completely reliant on government aid to survive. This included small numbers of people on welfare or in government-run nursing homes. But that has changed. As of February 24, 2020, under Trump’s new regulations, public charge rules penalize many immigrants who use–or may someday use–a whole list of benefits, including federal Medicaid, welfare, food stamps, and federal housing subsidies.

Not surprisingly, the Trump regulations were challenged in court as soon as they were announced. Some of the pivotal lawsuits were initiated by Make the Road New York, working with other advocacy groups. However, in January 2020 the Supreme Court refused to stop implementation of the Trump rules while the challenges work their way through lower courts. In April, the Court turned down a request to freeze public charge regulations during the pandemic. The legal battle continues.

Unless the new regulations are overturned, they will disqualify large numbers of people from getting green cards and protected legal status. Relatives will be prevented from joining their families in the US. There will be additional deportations. Immigrants will not access needed social assistance programs–even those they might still be eligible for.

All the while, millions of immigrants are left trying to figure out exactly how public charge rules are being enforced, and how their families might be affected later.

In Part 2 next week, we will look at who is not directly affected by the rule change, who is, and how.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

- Support Congresswoman Grace Meng’s No Public Charge Deportation Act, endorsed by over 50 immigrant rights groups

- Keep up with the latest public charge news; consult the Legal Aid/MTR screening tool and attorney referral guide

- Fight to expand permanent legal status for migrants

2. The Perception of Protests in Pandemic Times

Anti-Trump protests with far more attendees in a single day than all of April and early May’s #ReOpen events … passed with far less attention in the national press. (Vox)

Protests aim to bring attention to an issue so that attention can bring about social change. When the new Trump administration announced its first travel ban against Muslims in January 2017, thousands of protestors rapidly gathered at NYC airports, drawing critical public attention to the issue. Within 24 hours, a federal judge in NY issued a temporary injunction and the ban was lifted.

Naomi Wolf notes that an effective protest disrupts business as usual — so how does protesting change when the entire planet is disrupted? When there is no business as usual?

Immigrant rights groups in New York and New Jersey have taken to their cars in “driving protests” with hand-written signs in every window, driving slowly in caravans, honking horns, and flashing lights, to draw attention to immigrant detainees locked in detention centers during the pandemic. Cosecha organized a month of #FreeThemAllFridays with bike and car rallies to demand people’s release from ICE detention. Immigration activists gathered at an elevated station on the 7 train in Queens to unfurl banners– “Fund Excluded Workers”, “ Cancel Rent Now”, and “Free Them All”. On May Day, the Laundry Workers Center coordinated with nail salon workers, street vendors, domestic workers, cab drivers, and other workers for an hour of storytelling streamed live with Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Make the Road and NICE have also held COVID vigils for #NamingTheLost, remembering those who are lost to us by projecting their names on the side of a building.

During the past month of stay-at-home orders, national media has paid far more attention to small numbers of white protestors with assault weapons–many purposefully not wearing protective face masks, screaming at police and public officials–than they ever paid to large immigrants rights protests over the last year organized by groups like “Lights for Liberty” and “Families Belong Together”. One of Trump’s advisors, Stephen Moore, actually celebrated ‘anti-lockdown’ protestors, which include white nationalist militia members, by trying to associate them with the historic action of Rosa Parks.

For the first time since stay-at-home orders launched in New York in late March, up to ten people may now join for “non-essential gatherings.” While Governor Cuomo initially excluded protesters from his May 21st executive order, he reversed course under threat of a lawsuit by the New York Civil Liberties Union. Up to ten socially-distanced protesters may now gather … JHISN asks our readers to share with us on facebook and twitter the creative forms of protest-in-a-pandemic they are seeing locally.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

- Use social media or contact the editors of your favorite newspaper to generate better coverage of immigrant justice protests.

- Find where your skills are in this set of strategies for sustainable protest, then offer your skills for free to an activist group.

3. “In Their Own Words”– Latinx Immigrant New Yorkers and the Impact of COVID-19

Make the Road NY’s recently-released survey, Excluded in the Epicenter: Impacts of the Covid Crisis on Working-Class Immigrant, Black, and Brown New Yorkers, offers an invaluable and devastating picture of local communities reeling from the pandemic. Based on 244 phone interviews with mostly Latinx immigrants in and around NYC, the report reveals in careful empirical detail the intersecting crises faced by respondents: of work and income, housing, illness and death, education, and emotional health.

Mapped out in charts, graphs, interview excerpts, and biographical stories, the unmet needs of immigrant New Yorkers are staggering. While one in six respondents have already lost a family member to COVID-19, and four in ten report family members with COVID-19, less than half believe they have received the medical attention that they or their loved ones need. With 92% of respondents living in households where at least one earner has lost a job due to the crisis, only 5% have received unemployment benefits in the past month. Among the two-thirds of respondents experiencing depression and anxiety, nearly half do not know where to go for help. With 89% of respondents worried about how they will pay their rent, only 15% have received any form of government assistance.

“If we don’t die from the virus,” said one member, “it will be from hunger.”

The report also spotlights the experiences of youth—one-third of respondents were 24 years old and under—almost all of whom spoke of the toll the crisis is taking on their mental health:

It’s been hard! My brother and I are in college and my younger brother and cousin are in high school and elementary school. It’s very stressful. All of us are at home so it’s packed and it’s hard to concentrate. A sleep schedule has been hard to maintain. Dad and Grandma tested positive for COVID-19 and there are people in the house that are not obeying the social distance norms. Mental health issues as a student have been hard for me to deal with and getting help has been difficult because it’s not something I’ve navigated before.

Nearly one-quarter of young people reported that their experience with remote learning was “poor” or “very poor,” due to barriers including internet access (38%), no devices (42%), lack of school support (34%), or parents working (18%).

What would a ‘true recovery’ from this crisis look like? Excluded in the Epicenter ends with concrete policy recommendations and political demands that would help build a just society in which immigrant communities are, always, essential and empowered.

WHAT CAN YOU DO?

- Support Make the Road NY’s campaigns for the NYState Excluded Workers Fund, the #CancelRent campaign, and federal passage of the Health Care Emergency Guarantee Act.

- Read and circulate the full report, Excluded in the Epicenter

We wish you health, strength, and care as the crisis transforms and continues. The rich, complex fabric of our neighborhood has been torn. We hope that solidarity is one means of repair, together with new forms of connection.

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.