Dear friends,

Two years ago this month, Covid-19 hit the US. Our neighborhood in Central Queens quickly became a deadly epicenter of the global pandemic. For some of us that time may seem far away or a bit unreal; for others of us, including those who lost beloveds or who continue to suffer Covid’s lingering grip, the story has not ended. Memories remain vivid and losses are still grieved.

Our newsletter highlights the ongoing struggle for economic justice as the immigrant-led fight for pandemic aid marches straight to the steps of the state capitol. And we take a careful look at the inequalities and structural racism that shape how refugees are welcomed—or not—as millions of Ukrainians join the radical displacement and dispossession experienced by tens of millions fleeing Central Africa, the Middle East, Central America, and the Caribbean.

Newsletter highlights:

- #FundExcludedWorkers Now!

- Refugee Politics: Who is Welcome? Who Is Excluded?

1. #ExcludedNoMore Launches ‘March to Albany’

“This International Working Women’s Month, how will New York state care for domestic workers, restaurant workers, home health aids, retail workers, grandmothers, mothers, aunts, daughters, sisters, wives? …. The pandemic has shown us time and again that when a crisis hits, it’s our communities who fall through the gaps in the social safety net.” – DRUM (Desis Rising Up and Moving), 03-14-22

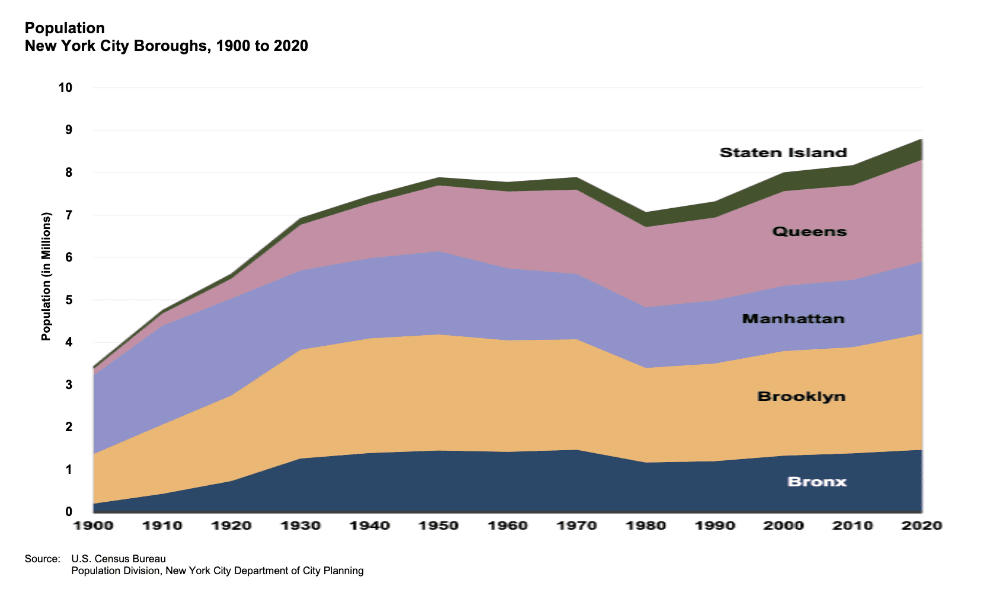

For those of us included in the pandemic social safety net who benefitted from supplemental unemployment insurance, stimulus checks, or remote work from home, the distance between NYC and Albany can be measured in hours or the price of an Amtrak ticket. For undocumented immigrants systematically excluded from the social safety net, the 150-mile distance to Albany is measured this month in activist days and a strategic itinerary through the districts of key state leaders. ‘March to Albany,’ organized by the Fund Excluded Workers (FEW) coalition, kicked off on March 15 in Manhattan with a march to the Bronx, and a demand for $3 billion in this year’s state budget for immigrant New Yorkers left out of pandemic aid.

FEW won a historic victory a year ago when their 23-day hunger strike helped secure a $2.1 billion Excluded Workers Fund in the NYS budget to assist eligible immigrants, many of whom had not received a single dollar in federal or state pandemic support. The fund was life-changing for tens of thousands of New Yorkers who successfully applied, including thousands of residents in Queens.

But the fund ran out of money barely two months after it launched in August 2021, with an estimated 95,000 applications still pending. Tens of thousands of people never even had a chance to apply before the fund closed down. Activists report that up to 175,000 immigrants remain effectively ‘excluded’ from funding for which they are eligible, and which they desperately need.

Immigrant justice groups, led by FEW, are mobilizing to right that wrong by securing billions for the Excluded Workers Fund in this year’s state budget. On March 8, hundreds of Deliveristas on bikes and scooters, along with domestic workers, street vendors, house cleaners, and taxi drivers, stopped traffic on the Manhattan and Brooklyn bridges, rallying to demand an additional $3 billion for the Fund, and a permanent unemployment insurance program for undocumented immigrant workers in NYS.

With less than three weeks to go until the state budget is finalized, ‘March to Albany’ is routing their #ExcludedNoMore campaign through the home district of Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, as part of a rolling cascade of actions around the state. On March 23, they will march into Albany to bear witness to the contributions, and needs, of essential and excluded workers. JHISN is one of over 120 organizations–along with local groups DRUM, Chhaya CDC, Adhikaar, and Damayan Migrant Workers–that endorse the Fund Excluded Workers (FEW) campaign. Join us in the urgent fight for budget justice in Albany!

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Please sign the petition and consider making a donation to support the Excluded Workers March to Albany.

- Raise your political voice for a permanent solution to gaps in the social safety net, and for Fund Excluded Workers’ plan to expand unemployment insurance for low-wage workers in NYS.

2. Equity and Justice for All Refugees

“I think the world is watching and many immigrants and refugees are watching. And how the world treats…Ukrainian refugees should be how we are treating all refugees in the United States.” –Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, The Rachel Maddow Show, 03-01-22

As of March 14, more than 3 million Ukrainians have fled the brutal Russian attack on their country. The EU says that the invasion could end up displacing over 7 million people in “[w]hat could become the largest humanitarian crisis on our European continent in many, many years.” It has asked all member states to grant asylum to Ukrainian refugees for up to three years.

European countries are eagerly stepping up to address the crisis. News media are full of heartwarming stories: “Moldovans Open Hearts and Homes to Refugees,” “Britain Announces ‘Homes for Ukraine’ Program to Sponsor Refugees,” “Berliners Open Their Hearts and Homes to Those Fleeing Ukraine Conflict,” “Map Showing Number of Polish People Willing to Accept Ukrainian Refugees in Their Homes Is Giving Everyone Hope”—a seemingly endless outpouring of sympathy and, even more important, material assistance.

What we are not hearing is familiar complaints about refugees “burdening” the receiving states; instead, only humanitarian concern and a willingness to share. This is inspiring; it is exactly how a global community should react to a vulnerable population running for their lives. So why does this response seem to only apply to white people?

Over the past 11 years, 6.8 million Syrians have become refugees and asylum-seekers from a war just as bloody as Ukraine’s. Except for Germany and Sweden, most countries in the West have refused to shelter them in significant numbers. Millions of refugees have tried to enter Europe because of deadly violence in Afghanistan and Iraq. They have faced “a backlash of political nativism” in the same countries that now welcome Ukrainians.

“The military in Hungary is allowing in Ukrainians through sections of the border that had been closed. Hungary’s hard-line prime minister, Viktor Orban, has previously called refugees a threat to his country, and his government has been accused of caging and starving them.

“Farther West, Chancellor Karl Nehammer of Austria said that ‘of course we will take in refugees if necessary’ in light of the crisis in Ukraine. As recently as last fall, when he was serving as interior minister, Mr. Nehammer sought to block some Afghans seeking refuge after the Taliban overthrew the government in Kabul.

“‘It’s different in Ukraine than in countries like Afghanistan,’ he was quoted as saying during an interview on a national TV program. ‘We’re talking about neighborhood help.’” –New York Times, 02-26-22

Horrifying stories are emerging of Polish border guards assaulting and ejecting refugees from Africa, while simultaneously welcoming white Ukrainians. The Ukrainian military has also reportedly discriminated against non-white refugees, sending them to the back of the line in train stations and at border posts as they try to flee the war.

And then there is the US. The Biden administration and Congress are urgently discussing how to help Ukrainian refugees. Almost overnight, billions of dollars have been allocated to help them get shelter and services in Europe. The president says “we will welcome Ukrainian refugees with open arms” if they come to our borders. He has already extended Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to Ukrainian immigrants now in the US. Some Ukrainians are apparently being allowed to cross freely into the US from Mexico. This is admirable.

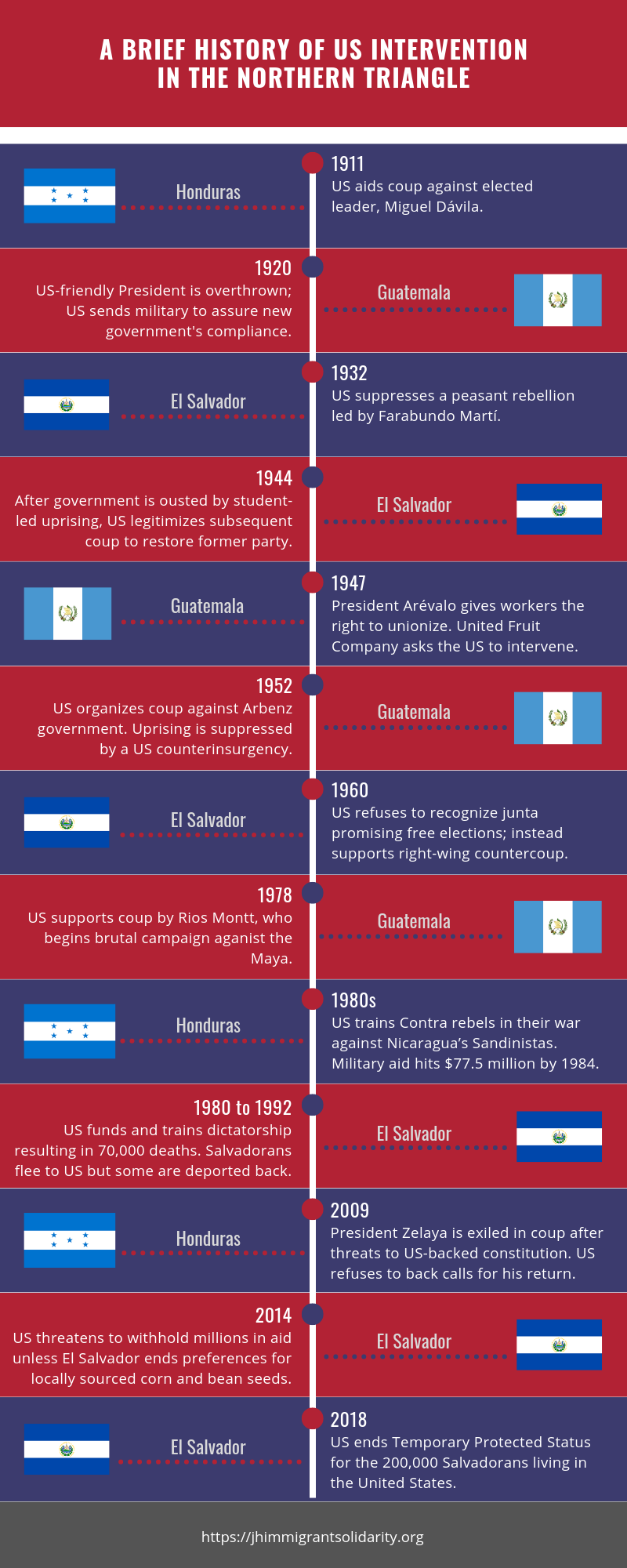

But this is the same government that turned away over 1,100,000 asylum-seekers last year, using the phony pretext of Covid-19. The same government that forced tens of thousands of Haitian asylum seekers onto deportation planes, back into the deadly chaos they had risked their lives to escape. The same government that illegally ejected hundreds of thousands of refugees from Central America who are fleeing the violence, destitution, and climate disasters caused in large part by the US itself. These refugees now face vicious abuse while stranded in Mexico.

Will the massive upwelling of support for imperiled Ukrainians transform the poisonous discourse about refugees in Europe? In the US, will the widespread racism towards refugees of color, thrown into stark relief by the Ukraine crisis, finally give way to a fuller respect for universal human rights? We can hope so. And we can fight to make that happen.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Support Haitian refugees through Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees. Call, email, and tweet to stop the racist deportations of Haitians.

- Sign the petition demanding TPS for 40,000 endangered refugees from Cameroon.

- Hundreds of immigrant justice groups are demanding an end to using Title 42 to expel and deport refugees at the southern border. Join the HIAS webinar on the humanitarian impact of Title 42.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.