Dear friends,

It is a pleasure to bring you news of the local and the uplifting. We offer you two stories—both closely tied to Jackson Heights—from the beating heart of immigrant justice and immigrant culture. First, we highlight the work of a local grassroots advocate working to smooth the arrival of new migrants to NYC. Next, we look at two decades of dance and music training offered by the Pachamama folklore program here in our neighborhood.

Newsletter highlights:

- Supporting local immigrants one case at a time–Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo

- Immigrant arts @JH: Peruvian folk music, and dance

1. Immigrant Support on the Street and in the Basement

“You are not going to win. You can apply, these are the benefits of applying. Statistically, you are not going to win.”—Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo (In conversation on 34th Avenue with JHISN)

Last year Nuala O’Doherty-Naranjo assisted over 2,000 families apply for asylum and start a new life. From her perspective, immigration paperwork is straightforward but managing expectations is not. Many new immigrants think having a lawyer guarantees success. Nuala points out that people with lawyers are more likely to win because lawyers only select winnable cases. Her kids call her the Dream Crusher because she warns everyone they are unlikely to win their asylum cases. Nonetheless, she presents asylum paperwork preparation sessions in her home basement for new immigrants who don’t qualify for such support elsewhere.

Nuala’s social media posts focus on community involvement, from gardening events in Jackson Heights to lively gatherings on the 34th Ave Open Streets. Amid these posts, she highlights immigrant support initiatives: the NYC Green Clean cooperative she started ensures home cleaners receive 100% of service payments; the many English language classes taking place throughout Jackson Heights; and instructions for the asylum paperwork sessions she provides.

Three mornings every week, new immigrants gather around tables on the 34th Ave Open Street, across the road from P.S. 149. Volunteers, who recently went through the process with Nuala, distribute information flyers in Spanish and handle a basic intake process. From about 50 attendees each morning, they identify around 20 who then move to Nuala’s home basement where they work until midnight.

In the basement, she outlines a plan for their future:

- Complete the Application for Asylum—she shares a draft copy of the document, translated to Spanish and annotated to guide people to complete it accurately.

- Attend English classes for five months—she has a map of where to go.

- File the request for a social security number and work authorization—they become eligible when the court does not rule on their asylum application within 150 days (which it never does due to the case backlog).

- Prepare a resume—apply for stable work with a union, hospital, or school system instead of taking occasional construction work, or working as a service provider for individuals/families.

While discussing her process, as we sit outside PS 149, Nuala greets passersby in Spanish but confesses that her Spanish is terrible. If anyone wants to volunteer assistance, she says, they must be able to speak the language, especially if editing personal stories. But, what she really needs from volunteers are financial donations, like the Facebook fundraiser by Cordelia Peterson, so that all the asylum applications can be printed. She bought cheap printers and bleeds toner onto a case of paper every week. Community members who want to volunteer their time can also be helpful if they bring food, and can keep any children occupied with play.

Nuala critiqued the city’s failure to prioritize filing asylum paperwork when the recent influx of immigrants began and instead focused solely on finding shelter. Her prodding for action resulted in guidance from the Mayor’s office telling new immigrants to call 311 for asylum paperwork assistance. When that quickly overwhelmed the 311 system the city shifted responsibility to the Red Cross. By Nuala’s own estimate, the Red Cross, with millions of dollars to support their work, has submitted just three times the number of applications she has ushered through—while she spends about $800 a week from her own dwindling funds.

Nuala does not restrict her work to one Jackson Heights basement. In Brooklyn, she works with a group of immigration lawyers, whom she plans to urge to write group briefs instead of individual applications. Group briefs can be used by multiple people in similar situations thus reducing the time required for each individual’s application. In Manhattan, she started the Asylum Seekers Assistance Program with Father Julian at the Church of St. Francis of Assisi, whose Manhattan volunteers spend an entire day working on a single person’s application. She is also starting to work as a counselor at Voces Latinas, allowing her to support people facing homophobia in addition to challenges due to immigration status.

As we wrap the conversation we discuss her motivation to do this work. “It’s gotta be done. It just needs to be done. Someone needs to do it…I can do it,” Nuala says. “I thought I’d do it until the city started doing it, but the city only does people who are in shelters—and then they kicked everyone out of the shelters.” It still needs to be done.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Provide support through a donation or gift to the Jackson Heights Immigrant Center shopping list.

- Follow and elevate the work of Voces Latinas.

- If you have an entry-level open position that can be filled by Nuala’s volunteers, contact the Immigrant Center.

2. Pachamama: Twenty Years in the Neighborhood

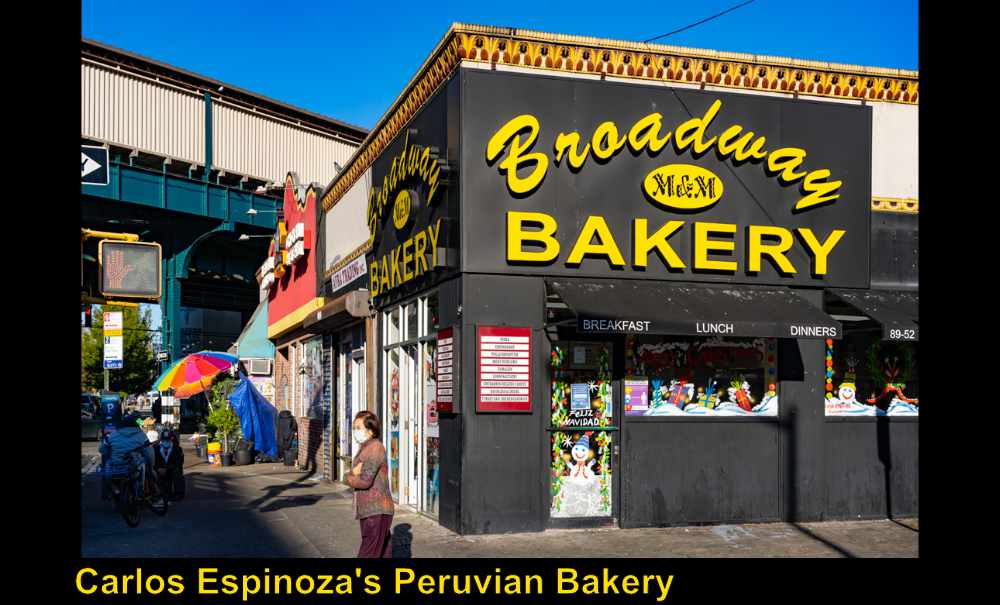

Every spring and fall, children in our neighborhood get free Peruvian folk music and dance classes. Pachamama’s folklore program attracts multigenerational families, who bring their children and grandchildren to learn about their heritage. By sponsoring these classes, Pachamama Peruvian Arts has played an important role in uniting the dispersed immigrant Peruvian community in New York.

Pachamama started as an initiative of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance (CTMD). It was ”the Center’s first long-term project to focus on a South American community.” The Peruvian Folklore Project centered around two accomplished artists and folklorists. Luz Pereira, a graduate of the first School of Peruvian Folk Music and Dance, was also part of the cast of “Perú Canta y Baila,” which won several international folklore awards. And Guillermo Guerrero, an expert in playing traditional Andean music, who expressly traveled to different cities in the Andes region to obtain his authentic instruments. Guerrero and Pereira would be the principal teachers of the Project.

The CTMD introduced the Project to the public in Flushing Meadows Park during the Peruvian National Holiday festival on June 28, 2003, at an event organized by Club Perú. CTMD set up two demonstrations, one featuring Marinera Limeña dance, and another where Andean music was played. A survey asked 100 participants if they would like their children to receive free folklore classes. The unanimous answer was yes. The place chosen was Jackson Heights; a neighborhood where several Peruvian families reside.

Pachamama taught Marinera Limeña and Andean music for the first time in January 2004, at PS 212, to children between 7 and 17 years old. Since then, Pachamama has rotated through other schools in the neighborhood, such as IS 145, PS 69, and has been teaching folklore at the Garden School for three years. Over the years, classes about the folklore of the three regions of Peru have been added, and more teachers have joined to teach cajon, singing and choir.

Marinera (“sailor” in Spanish) is descended from Zamacueca, a dance of Spanish origin. But in the 1860s, a Peruvian version mixed with Afro-Peruvian rhythms emerged, danced mainly in Lima’s port by Afro-indigenous-Peruvian descendants. At first, it was not allowed in the living rooms of aristocratic families, who considered it too sensual and flirtatious. That story changed after the term “Marinera” was adopted to give support to the Peruvian Navy who were fighting the Pacific war in 1879. Actually, there are many styles of Marinera named by region. Today, Marinera Norteña is considered a national dance of Peru, and annual competitions are held to choose champions by age group.

After several years of being funded by the CTMD, Pachamama Peruvian Arts was established as a separate non-profit, non-governmental organization. Luz Pereira continues as the Executive Director. There have now been twenty years of uninterrupted Pachamama activity. The program persevered even during the height of the pandemic, when classes and graduations took place via Zoom. Pachamama students have performed at different schools and institutions, such as Queens Public Library, Corona Plaza, the Queens Museum, and Queens Theater.

More than 2,000 children, mostly from Peruvian and partly-Peruvian immigrant families, have studied with Pachamama. Many of them continue to practice dance, music, singing, and theater. The program has awakened a sense of belonging and identity in many second-generation Peruvian immigrants. It has even encouraged tourism to Peru, as Pachamama students ask their families to learn more about their culture. Thanks to Pachamama Peruvian Arts, Peruvian cultural heritage is being valued and preserved in New York.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Follow Pachamama Peruvian Arts on Facebook to be informed about classes and events.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.