Dear friends,

In a time of so much political uncertainty, we are buoyed by the huge victory recently won by immigrant taxi drivers in New York City. After over 40 days of round-the-clock protest outside of City Hall and a 15-day hunger strike, workers danced in the streets to celebrate the historic agreement that will deliver dramatic debt relief to cab drivers. “We won,” announced Bhairavi Desai, head of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance which represents 20,000 taxi workers, and which led the public protest and hunger strike. With so many immigrant cab drivers who are residents and neighbors here in Central Queens, the win is a community victory and cause for collective hope.

In this issue, we are delighted to share a feature article on the milestones of culture and politics of Peruvian immigrants in NYC, written by JHISN member Rosalinda Martinez, who has lived in NYC for almost 20 years after immigrating from Peru. We also report on the latest news on national legislation to provide a pathway to citizenship for millions of immigrants. If you have been confused by recent headlines, we try to clarify the urgent stakes in what takes place—or does not—in the next several weeks in Congress.

Newsletter highlights:

- Peruvian Immigrants Make a Cultural Home in NYC

- Path to Citizenship Detoured, Once Again?

1. NYC Peruvians Stay Close to Their Roots

“We continue walking the Capac Ñan (the Inca Road). If the West hadn’t arrived, the Inca empire would have reached this land in the Northern Hemisphere. Tawantinsuyo would have extended from the south, in what is now Chile, and reached what is now Canada.” — Walter Ventosilla, director and screenwriter, Abya Yala (interview with the author)

Peruvians have a long and distinguished history. Those of us who came to live in New York have our own part of the Peruvian story to tell. Writing this article about Peruvians in NYC made me realize that we continue being who we are because we hold onto our ancestral culture.

Before I came to the US, I didn’t know much about this country. The first thing I heard was that “everybody loves Peruvian food in the US.” When I arrived in 2003, I tried to engage with anybody Peruvian. I went to all the Peruvian events I could find. There was the Hispanic-Latino Fair at Renaissance Charter School, the Peruvian Parade on Northern Boulevard, Mother’s Day and the closing events of Pachamama Peruvian Arts in a Jackson Heights school, the procession of the Lord of Miracles in Manhattan. I also discovered the biweekly newspaper, the Ayllu Times, as well as writers, poets, journalists, and bloggers.

For a long time I wished I had a group, so one day, in 2014, I walked purposefully on 74th St and turned into Diversity Plaza and saw a truck on the corner and people in line. It was a local exposition of paintings inside a truck (Art & The Commons). I borrowed my first painting to place in my room and met someone from the Humanist party in NY. I became involved in the movement for “Yes to the Peace Accord” with the guerrillas in Colombia, which Humanists supported. Then in 2018, I saw a table on 37th Ave, with a sign-up sheet for JHISN. I felt this was what I wanted to do. And here I am, answering requests for help from Latinos who write to us and doing Spanish translation for our JHISN newsletter and flyers. I’m giving to my community because the ayni (reciprocity) lives in me.

The Peruvian population in the US is about 700,000, concentrated in Florida, California, and New Jersey. Over 66,000 Peruvians are living in New York state. The majority live in Queens, Long Island, and Westchester, but there are many Peruvians also in Brooklyn and the Bronx. Some immigrants came originally with a visa, but most crossed the southern border. People who arrived in the US during the 1970s and 80s were mostly middle-class people from cities along the coast, mainly from Lima. After the 1990s economic crisis, there was a bigger influx of migrants from all over the country. Peru had slowed its path to industrial development and instead had become a major exporter of raw materials—and migrants. The outcome for immigrants often depends on the type of job they find here, having a relative or a friend, learning English, and also their character. According to the World Bank, Peruvian immigrants send almost three billion dollars in remittances back to Peru every year.

In New York, Peruvians have different beliefs and political opinions, but we are united by our roots. Quietly, our traditions continue to spread among our people in the US, especially our children and grandchildren. During the 1990s, the diffusion of our music and dances got a boost when talented people met and formed different musical groups. Pachamama Peruvian Arts was founded in 2004 in NYC, with the aim to preserve and perform traditional Peruvian music and dance. Its teachers offer free classes to students in Jackson Heights schools.

Another high point of Peruvian culture in New York is Abya Yala Arte y Cultura, which was started in 2006. Abya Yala puts on every year a theatrical representation of the Inti Raymi, a traditional religious ceremony of the Inca empire paying homage to Sun-Father (Taita Inti) in June, during the winter solstice in the Southern Hemisphere. Songs, dances, flowers, food, and chicha (corn liquor) are offered to Taita Inti by the Inca, with the hope that the sun will come again, bringing good weather to produce a lot of food from Pachamama, Mother Earth. We are proud that since 2007, a director, a playwright, actors, musicians, dancers, and volunteers have brought this fabulous spectacle to the public. In the aftermath of Abya Yala’s success, more cultural groups have been formed; some Peruvian teachers started their own academy such as Peru Andino NY.

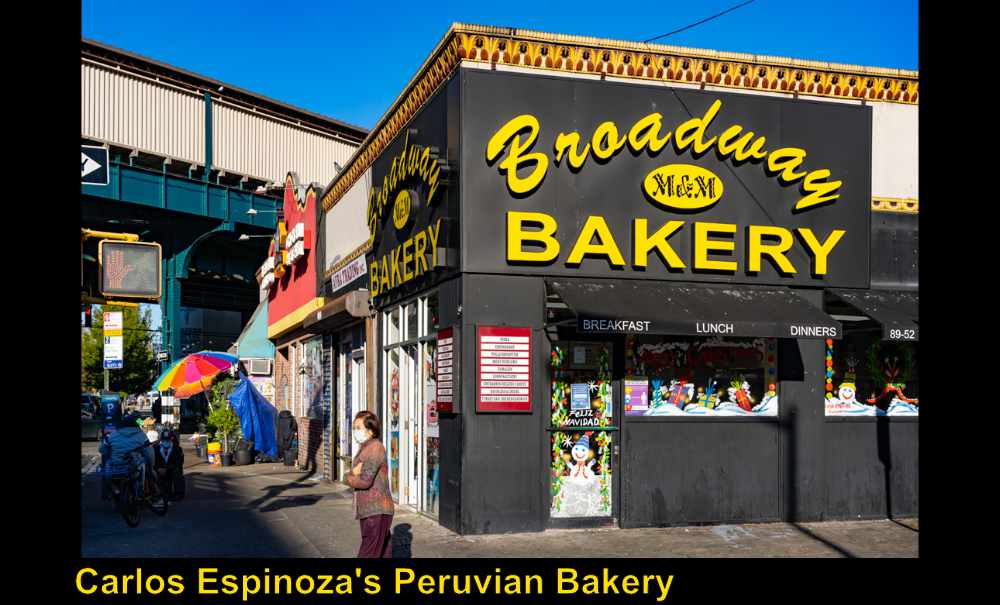

Ayni or reciprocity—to exchange work or goods—is in our genes and continues moving us. In April 2021, Peruvian bakery owner Carlos Espinoza was given an award by the Mayor of New York for his active role in supporting immigrants. Espinoza kept his business open in Elmhurst—in the epicenter of the epicenter of the pandemic in New York—which allowed essential workers to get food to go to work. He also distributed free food cooked by his mother to immigrants living in Elmhurst and Corona.

Peruvians have always been politically active. In 2016, there was a big Rally for “Keiko No Va” in Times Square organized and led by a Left movement called The Tri-State Coalition of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York and the “Keiko No Va” group, signaling that we didn’t want a Fujimori government ever again. Marcela Mitaynes, a tenant activist, was elected New York State Assemblywoman for Brooklyn District 51 in 2020, the first Peruvian to serve in the state Assembly. In our own land, Pedro Castillo, a rural Andean teacher and a union leader from Chota, Cajamarca, was elected President in 2021. This is a promising slap in the face to the powerful criollo descendants from Europeans who rule Peru but have turned their backs on the people, especially from the Andes and the forest.

There’s hope for Peruvians who identify themselves with our ancient origins, ethics, and values.

2. Another Black Hole for Immigrant Rights?

It’s important to have a path to citizenship for long-term security. All of our members would be affected by the outcome of what’s being decided in D.C. in the next few weeks. —Manny Castro, Executive Director, New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE)

The path to citizenship that Democrats promised to 11 million immigrants is on the verge of disappearing into another Washington, DC black hole. In recent weeks, House Democrats tried without success to include such a path in their massive “Build Back Better Act,” which is headed for a showdown vote in the Senate sometime soon. Specifically, they proposed that green cards would be offered to immigrants who had been in the US for more than ten years. This approach was similar to that used by Congress in 1986 to legalize the status of millions of immigrants who had lived in this country for several years.

To get the Build Back Better Act passed, Democrats have been counting on avoiding a Republican filibuster, which would require 60 votes to overcome—a virtually impossible task today. However, legislation that has major budgetary implications can be passed by a simple majority under the procedure known as “reconciliation.” It’s up to the Senate parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, to advise on whether the various provisions of the Act meet the standards for reconciliation. She has ruled against the green card proposals twice—because, in her controversial opinion, they didn’t mainly concern budgetary matters.

The Democrats could get rid of the filibuster, but they seem unwilling to take this action right now. There is also the option to overrule the parliamentarian’s decision on reconciliation by a simple majority vote. Although immigrant advocates have accused MacDonough of bias—she was once an immigration prosecutor—there seems to be no appetite for a confrontation with her among most Democrats. Instead, they are now discussing watered-down reforms that would fall far short of a pathway to citizenship.

One idea under serious consideration is to provide temporary 5-year protection from deportation and work permits for millions of immigrants, including Dreamers, agricultural workers, and some refugees or asylum seekers. This kind of short-term fix has been disastrous for Dreamers in the past, resulting in cycles of fear and insecurity. Depending on how negotiations proceed, “protected” immigrants might not even be eligible for public benefits, including health care.

Another reform under discussion is to “recover” and distribute more than a million green cards that have been authorized by Congress since 1992 but have gone unused. Under one version of this proposal, green card applicants now caught in the green card backlog could pay fees of thousands of dollars to speed access to permanent residency. Part of the thinking here was to create a budgetary impact that might survive the scrutiny of the parliamentarian.

Immigration advocates inside and outside Congress are lobbying furiously to keep substantive immigration legislation alive. They haven’t given up; some have promised to vote against the whole Build Back Better package if it fails to include meaningful immigration provisions. But pressure to pass the massive Biden bill in any form is also building.

Immigrant justice groups have organized a variety of demonstrations and pressure campaigns targeting DC lawmakers. Locally, NICE has been engaged in an extended campaign called “11 Days for the 11 Million,” a series of actions based in Times Square, pushing for “citizenship for all.” Immigrant mothers organized by the Movement for Justice in El Barrio gathered in front of Senator Gillibrand’s office last week with the same demand. The outcome of this struggle—with millions of immigrants’ lives and livelihoods at stake—remains to be seen.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

- Contact your Democratic Congresspeople and tell them to include citizenship for all in the Build Back Better Act.

- Donate to New Immigrant Community Empowerment (NICE), to support the fight for comprehensive immigration reform.

In solidarity and with collective care,

Jackson Heights Immigrant Solidarity Network (JHISN)

Follow @JHSolidarity on Facebook and Twitter and share this newsletter with friends, families, neighbors, networks, and colleagues so they can subscribe and receive news from JHISN.